Tension gripped my gut as I drove to a Mennonite church in Altona, Man., with an indigenous friend. We were doing a joint Sunday morning presentation about hydropower impacts.

I wondered if an indigenous person had ever been in that church. I debated making excuses for whatever suspicion, or worse, my people might direct toward him. I tried to muster grace.

It went fairly well, although in such settings one mostly encounters a silence that leaves much to interpretation.

That nerve-rattling experience repeated itself often between 1998 and 2001, when I worked on indigenous issues for Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) in Manitoba. And I know the tension is well-known to others who have been officially tasked with building bridges between Mennonites and indigenous people over the past 40 years.

Some Mennonites are warm and welcoming towards indigenous people, others are uncomfortable, and still others brim with accusation. A Mennonite politician once came into the MCC office to give me a blustery lecture.

Ultimately, I was left to explain to indigenous people that MCC’s commitment to them—a commitment they valued greatly—was limited by the reluctance of some donors to align with them, particularly when it came to anything deemed “political.” I was also left with some lessons about how to pursue cross-cultural understanding and how not to. And, of course, I was left with many enduring relationships with the Cree people I worked along side.

The task of building cross-cultural bridges is rewarding and intense.

For the past four decades, Mennonite organizations have given a small cadre of people this task. Some have worked right in indigenous communities, some have worked on specific issues and some have worked more generally at connecting indigenous and settler people groups through exposure trips, camping trips, speaking events, websites, books and the like.

I am blessed to know many of these people. That is to say, in part, that I come to this subject with a bias as deep as my relationships to friends and colleagues both Mennonite and indigenous.

The granddaddy of this work is Menno Wiebe, who led MCC Canada’s Aboriginal Neighbours program from 1974 until his retirement in 1997. He established an astonishingly broad and deep network of relationships with chiefs, grandmothers, artists, national leaders and every-day folk in indigenous communities from coast to coast. He created a tremendous amount of goodwill toward Mennonites.

Others have carried on that work in various ways and places, often, as in my case, with Wiebe as a beloved mentor and elder.

Now, after 40 years of official Mennonite-Indigenous engagement, perhaps it is worth taking stock. Where does the relationship stand? That is a difficult question, but some observations can be made.

Personnel

First, in terms of commitment of personnel, MCC offices across Canada employ seven people to do this work—some part-time, some not, with various changes pending. In the past, there were considerably more, including more people living in indigenous communities. Then there are other MCC programs that involve indigenous people, such as prison visitation initiatives. The Ottawa Office also addresses indigenous issues.

Mennonite Church Canada offices employ two people devoted to this work—one based in Winnipeg, one in B.C.—and others whose duties include indigenous-related programming.

Unfinished business

Second, the work is far from over and it remains controversial. Mennonites and indigenous people share a country, but our lives are remarkably separate. There are a few Mennonite churches in indigenous communities and I’m sure there are some indigenous people who attend non-indigenous Mennonite churches. Then there are Mennonites who encounter indigenous people outside Sunday morning. But for the most part, indigenous people are not found in our churches, our organizations or our living rooms. The gap to be bridged is wide.

And the footing on either side is delicate. Like many nations, Canada has profound guilt lurking in its national conscience. The entity we call Canada resulted from Europeans arriving here and slowly taking over from those who lived here before. The Europeans did some noble things and many ignoble—even genocidal—things along the way. Overall, Canada has worked much better for Europeans and others who have arrived since, than for its indigenous inhabitants. This is a fundamental element of our nation.

Earlier this year, James Anaya, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous People, reported on “the well-being gap between aboriginal and non-aboriginal people in Canada,” and the fact that it “has not narrowed over the last several years.” The glum litany of trouble in the report is by now a national cliché.

What moves it out of the realm of cliché for me is to drive through an indige-nous community, see children playing, and feel the aching reality that those beautiful children of God face far more challenges and much tougher odds than my own children.

I think the common knowledge of such disparity is profoundly—if often subconsciously—unsettling to many Mennonites. It evokes both positive and negative reactions.

Mixed emotions

Negative sentiment towards indigenous people is still common in Canada. Just look at the comment section of online news sources. For example: “Is the Globe and Mail going to promote my hash tag #paynomore for those of us fed up with paying for natives to do nothing but live off taxpayers their entire lives while being professional victims?”

Darryl Klassen, who is concluding 25 years with MCC B.C., says the “get over it mentality” towards indigenous people is still “pretty pervasive” in the church. A teacher in a largely Mennonite high school in Manitoba reports the same prevailing attitude among students.

At the same time, Klassen says there is a growing degree of understanding that our histories affect “the realities of today.”

It is hard to measure trends in Mennonite attitudes, but Sue Eagle is confidently optimistic about her job with MCC Canada’s Indigenous Work program. She says interest from MCC leadership and constituents has increased significantly in the last five years. The recent MCC Canada annual general meeting included a learning day focussed on indigenous relations. And Eagle lists positive involvements across the country.

“I have no fear for our program at all,” she says, after 10 years in the role along with her husband Harley.

Brander McDonald, who coordinates indigenous relations work for MC B.C., says that in his context dialogue is the only realistic goal. Any engagement beyond dialogue is not a realistic expectation. As for the work of promoting dialogue, he is honest about the ups and downs it entails.

Like Eagle, he repeatedly expresses appreciation for the support of leadership within the organization he works for.

Leadership and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

This increased interest among leaders is a third observation about the state of Mennonite-Indigenous relations.

A related observation would be the role of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in nurturing this interest. The TRC is a federally mandated process to address the Indian Residential School legacy. Numerous leaders within MCC and MC Canada have attended TRC events. This appears to have deepened official Mennonite commitment to indigenous work.

Don Peters, who heads MCC Canada, attended three TRC events. In an e-mail, he recounted sitting in a room of a thousand witnesses as residential school survivors told TRC chair Murray Sinclair of their often horrific experiences. Trained attendants walked the aisles offering tissues, water and support to witnesses overwhelmed by the stories. As a particular Dene woman told her devastating story, Peters says an attendant came over to him, asked if he was okay, and offered a tissue. “I took one and nodded,” Peters recounts.

MCC Canada is now working on a strategic planning process that will “build on the impact of the TRC for MCC involvement in Canada,” says Peters.

Willard Metzger, executive director of MC Canada, attended five TRC events across Canada. “That has really shaped me,” he says. “I have been impacted by the generosity of spirit of the indigenous community in sharing painful stories,” Metzger says, adding that stories were told not in a “blaming way,” but in the spirit of saying “you didn’t do it but you need to know this is what happened.”

Metzger says that for a church to have integrity in the Canadian context it must be “working at strengthening relations with indigenous people.”

He says Step 1 in that work is getting to know our indigenous neighbours. “A lot of the fear people have,” he says, “is because they don’t have any first-hand relations.” Next, we need to understand that the indigenous worldview is not “anti-Christian.” And ultimately Metzger says we need to move on to the “difficult conversations about land claims.”

But he says he can’t give a sense of whether MC Canada’s level of financial commitment to indigenous work will increase, decrease or stay the same.

MCC B.C. sent a wave of concern through the community of Mennonites working on indigenous relations this year by announcing the dismissal of Darryl Klassen, who coordinated the Aboriginal Neighbours Program for MCC B.C. for 25 years. (See “MCC B.C. ‘refocusses’ Aboriginal Neighbours program, releases staff” sidebar on page 6.) While MCC B.C. is simultaneously “reaffirming” its commitment to indigenous relations, some people I spoke with fear that MCC B.C. may not have a sufficient understanding of the nature of the work and the implications of sidelining the person that has personified the relationship in B.C. for so long.

The decision is a blow to McDonald, who works closely with Klassen and is indigenous himself. He says the decision has made him hesitant to risk his reputation in his own community. He’s reluctant to enter relationships on behalf of Mennonites when the church may not stand by those relationships.

Despite the shake-up in MCC B.C. and budgetary uncertainty at MC Canada, Mennonite leaders in general appear to be more personally engaged in indigenous issues than has been the case in the past, in part because of the TRC.

Corporate culture

This trend may stand in tension with another trend noted by Darryl Klassen. While speaking with relative equanimity about his personal situation, he laments what he sees as a “a significant change in the nature of MCC” across the country. He says that when he started, MCC was “like a family,” but now staff are being “squeezed” into a “corporate” or “government” model marked by more formality, narrower requirements for reporting, more emphasis on numbers, and more “hierarchy.”

Klassen feels the new structures are poorly suited to indigenous relations work. Beyond that, he feels the changes are “taking the heart out of MCC.” Klassen says, “The beauty of MCC has always been its horizontal structure, and trust and integrity and honour within MCC and our relationships.” Now he sees a “negative view” towards these “older ways.”

MCC B.C. board chair Len Block says the essential task in terms of indigenous work is “keeping in touch” and “making sure we have a good program with results that show we are making a difference.”

But how will a results-oriented posture affect relationship-building efforts?

Elaine Bishop served with MCC in Little Buffalo, an exceptionally down-trodden Cree community in northern Alberta. In 1996, at the close of her four years of tireless, passionate work, I asked her about ongoing MCC involvement in the hurting community she so loved. She said MCC needed to stay there to “witness the disintegration.”

Bias

That raises a question about the theological and spiritual foundations of this work. Is our goal to encounter Jesus on the messy margins of society? Do we seek our own transformation through long-term relationships? Do our programmatic plans leave room for accompanying people through prolonged periods of failure and disintegration? Do we want successful programs or friends?

At the same time, indigenous people need more than friendship. They need a fairer society. They desperately need a certain sort of results. One message Klassen is getting from them is that now is the time for Mennonites to “walk the walk.”

Mennonites are well positioned to play a role in making change, but the only path to those sorts of results is through long-term relationships that nurture the incremental mending of the torn fabric of society.

As for the resistant attitudes within the church, the dialogue must face the many complicated, nuanced issues related to indigenous people: dependence, dysfunctional governance, a victimization mindset. These things, and their oppo-sites, exist. But they look very different if you are sitting with an indigenous friend, instead of ranting from a distance.

Richard George, an indigenous friend whom I was honoured to have in my living room many times when I lived in B.C., and who I’m sure has shared many laughs with Darryl Klassen, told me that Mennonites need to understand why things are the way they are in indigenous communities.

We need to understand why people are drunk, or mad at the church, or unemployed, or more “political” than we may like. Our bias should be towards understanding. Our bias should be towards relationship.

Willard Metzger says of his experience with indigenous people: “They want to be good neighbours, they want to figure this [relationship] out. . . . Why wouldn’t we, as God’s people, want to respond positively to that?”

For reflection and group discussion, go to the discussion questions related to this article.

See also: MCC B.C. ‘refocusses’ Aboriginal Neighbours program, releases staff

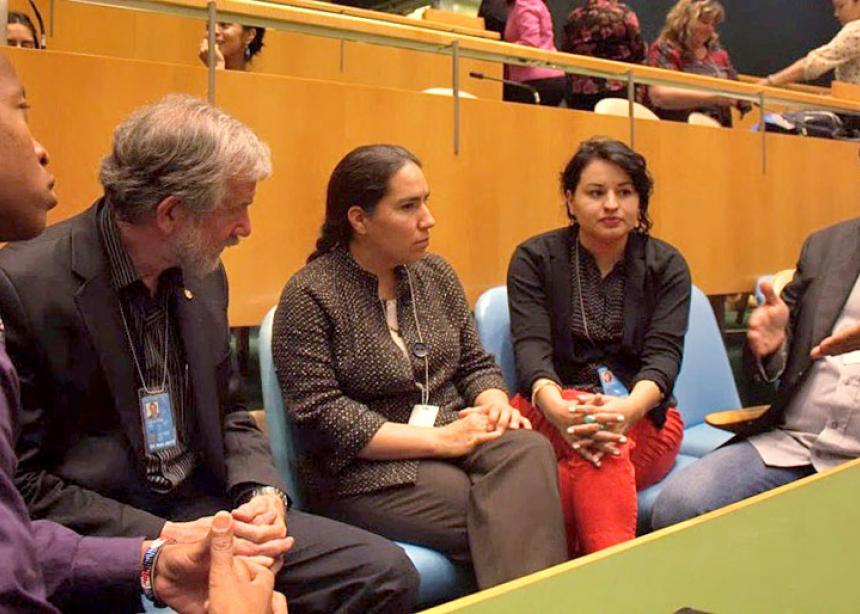

Harley Eagle, right, Mennonite Central Committee Canada’s co-coordinator of Indigenous Work with his wife Sue, speaks with other MCC staff and partners at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. (Credit: courtesy of MCC UN office)

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.