Martyrs Mirror is newer than the Bible and longer than some copies of it.

Like the Bible, though, the book has a powerful message for today, said James Lowry, a Mennonite historian from Hagerstown, Md. “Persecution, dungeons, shackles, chains are not something in our experience,” Lowry told an audience at the June 8-10, 2010, “Martyrs Mirror: Reflections Across Time” conference at Elizabethtown College.

Yet people today live in a materialistic age, as Dutch Mennonites did in 1660, when Thieleman van Braght revised and added to previous books and records about Christian martyrs, aiming to spark spiritual renewal, Lowry said. “Martyrs Mirror is the correct medicine for 21st-century Christians, and especially for Mennonites,” Lowry suggested.

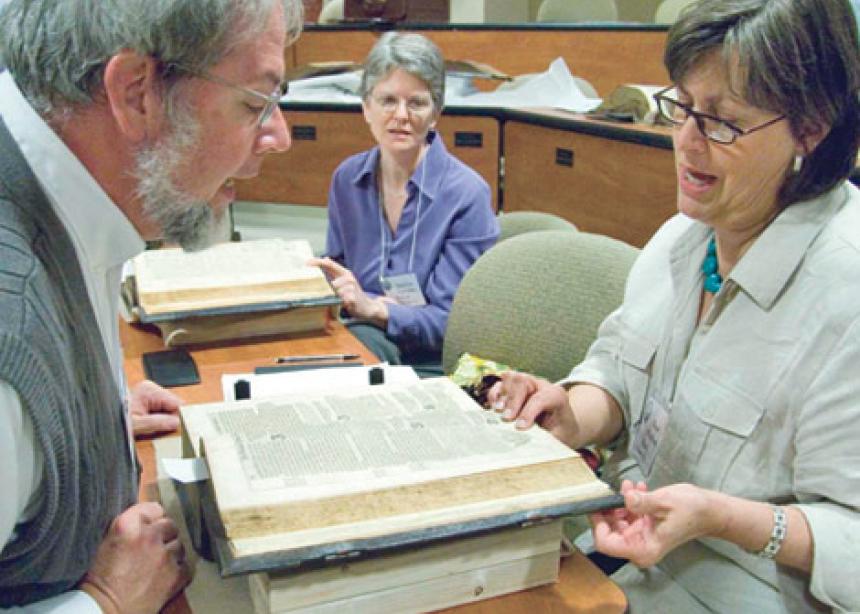

More than 60 people from across the spectrum of Anabaptist-connected groups, as well as scholars from other traditions, gathered for the event marking the 350th anniversary of the 1660 edition, called The Bloody Theater of the Baptism-Minded and Defenseless Christians, which tells of martyrs from the early church and persecuted groups in Europe through to the Anabaptists of the 16th and 17th centuries. The 1685 edition added Jan Luyken’s etchings depicting events described in the text.

One story tells of Anneken Jans, drowned in 1539 in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, after she was arrested for singing a hymn in public. Another remembers Dirk Willems from Asperen, the Netherlands, who escaped from prison but stopped running to rescue his pursuer, who had fallen into an icy pond, only to be recaptured and executed in 1569.

“These are heroic, mythic tales designed to inspire allegiance to Mennonite identity and conformity to its ethic of nonviolence at any cost,” said Julia Spicher Kasdorf, professor of writing at Penn State University in University Park.

Nurturing nonresistance

In the early 1740s, German-speaking Mennonite immigrants to Pennsylvania ended efforts to gain exemption from military service after colonial authorities directed them to take their request to the king’s officials in England. “Rather than attempt to change public policy, they would publish the Martyrs Mirror,” Kasdorf said.

In 1748-49, Mennonite leaders commissioned a new edition of the tome in Ephrata, Pa. Several hundred copies remained unsold. During the Revolutionary War, the Continental army confiscated some of them to turn the paper into gun cartridges.

After the Ephrata edition, American Mennonite leaders would reprint Martyrs Mirror during times of war, to inspire the preservation of nonresistance, Kasdorf said. “The martyr becomes an alternative soldier, so the pacifist is not seen as a coward, but as a hero,” Kasdorf said.

Martyrs Mirror has power even for those who have not read it, Kasdorf said. She finds it difficult to read herself, in large part because of the antagonistic language used to describe members of the state churches who viewed Anabaptists as heretics. “It can get in the way of conversation with other Christians,” she said.

In the 16th century and today, heresy and martyrdom are a matter of definition, said Sarah Covington, professor of history at Queens College at the City University of New York, N.Y. “One person’s martyr is another person’s terrorist,” she said. “In a sense, martyrs are religious extremists, since they die for what they understand to be one unified truth.”

“Martyrdom resists an ecumenical age like ours,” Covington said. “[Martyrs] represent a pure faith, a faith not watered down.”

Public witness

In Martyrs Mirror, women as well as men testify to their faith and understanding of truth. “Early Anabaptist women facing arrest and execution boldly used their voices and words to shape hostile situations to their own ends,” said Jean Kilheffer-Hess of East Petersburg, Pa., who collects and studies oral histories.

Humility shaped the early Anabaptist understanding of suffering and martyrdom, said Andrew Martin, a doctoral student at the Toronto School of Theology, Ont. “Central to the Anabaptist ethical heritage is a self that was transformed on the journey toward ultimate truth through an encounter with God and the expectation of meeting him face-to-face in death,” he said. “Anabaptists have left us a spiritual legacy that is foundational for Christian ethics today.”

John D. Roth, professor of history at Goshen College, announced that the Mennonite Historical Society in Goshen, Ind., is planning a conference on Martyrs Mirror in 2012, at which time the possibility of extending the collection of accounts to the present day will be discussed.

Meetinghouse is an association of Mennonite and Brethren in Christ publications. Celeste Kennel-Shank is assistant editor of Mennonite Weekly Review, a Meetinghouse publication.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.