For 500 years the Mennonite narrative has been dominated by stories of forced migration, escapes from persecution and the search for a place of refuge—often desperate quests for freedom to practise our faith or chosen lifestyle, and the burning desire to live and raise our children in peace. Ethno-cultural, religious and economic factors were usually fully intertwined.

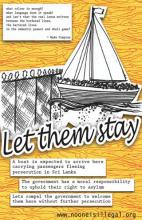

For several weeks now, Canadian newscasts have focused on accounts of Tamils seeking freedom from persecution in Sri Lanka and a new life in Canada by arriving on the British Columbia coast aboard the barely seaworthy MV Sun Sea. The response from Canadian citizens has been mixed, but dominated—in the media at least—by anger against those who would take desperate measures to seek refuge with us.

Clearly, if anyone is able to understand the Tamils, it should be Mennonites. Yet even among our own one hears voices that have been less than charitable.

We need not go back five centuries to evaluate the Mennonite experience, but only examine our own family’s journey to Canada. If we have not come here as refugees or immigrants, we have almost all been told stories first-hand by parents and grandparents who have, or have read the stories from an ancestor’s diary.

Whether Mennonites came to escape war, starvation or persecution; or to seek land, religious freedom or a peaceful future for their children—they came because they were welcomed here. So let’s look again at the accusations being thrown out by Canadian citizens against the Tamils and re-evaluate them from our own history.

Accusation 1

The Tamils are not really refugees because they cannot be fleeing for their lives. Their situation was not that bad. After all, they lived in a democratic country in which they just happened to be the minority.

Stories of my own family’s experience—Russian Mennonites who came to Canada from the Soviet Union via Germany and Paraguay—help me conclude rather quickly that these Tamils did not embark on their stressful three-month voyage as a vacation cruise. Circumstances will have been dire, dangerous and urgent to spark such a risk-filled venture.

When people decide to flee without sanction, and thereby imperil their own lives and the lives of their children, it is always an excruciating decision, one ultimately embarked upon because the alternative of staying put is worse. The devastation of the province in which the Tamils lived parallels the devastation of the Mennonite colonies in Ukraine after the civil war—and in some areas is much worse.

Accusation 2

These are not refugees, but economic migrants, because refugees are poor and the Tamils paid $30,000 or more per head in order to get on the MV Sun Sea.

It is unlikely that most of the refugees paid for their voyage from their own funds, but rather more likely that the money was raised by their community and either lent or given to them. According to some, that makes it even worse, since it suggests the involvement of criminal elements.

How quickly we forget. Perhaps words like Reiseschuld (travel debt) no longer mean anything to us. When Mennonites came to Canada, in almost every case it was other Mennonites who were already here who raised the vast funds required, or who took out loans in order to pay for the travel by ship and train for those who were coming. Or it was Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) that contracted for ships to transport Mennonites across the ocean. And MCC’s money came from the Mennonite community.

Accusation 3

The quality of the on-board organization by these Tamil refugees to preserve sanitary conditions and proper order, including sleeping quarters, proves that it was indeed an illegal smuggling operation organized by criminal elements and possibly terrorists.

Once again, the story of my family and the accounts of others suggest that refugees usually try to organize quickly, while on the run, in order to preserve the health of both the immediate family and the refugee community, and to prevent the chaos that can spell the difference between success and failure of the desperate journey to gain refuge.

For this reason, I am impressed by the on-board organization of the Tamils and believe they should be lauded for creating survivable travelling conditions in circumstances that could have easily produced a humanitarian disaster otherwise.

Accusation 4

They are really terrorists masquerading as refugees—or at least there are terrorists among them.

It is easy to demonize and cast aspersions on the stateless and the homeless—those without a fixed address, lacking the supportive voice of a national government to lobby on their behalf, knocking on our doors and appealing to our human compassion to let them dwell with us in safety.

People did the same to Mennonite refugees at various times. In 1929, when between 13,000 and 16,000 Mennonites gathered in Moscow seeking refuge in Canada and the U.S., newspaper editorials across the country argued against accepting these Mennonite refugees from the Soviet Union.

The Edmonton Journal and the Regina Morning Leader argued that these Mennonites were not good citizens. Even the New York Times scoffed at them as “prosperous” community members, suggesting on the one hand that they were really economic migrants and, on the other, that they were also really “in their time . . . good revolutionists,” revolutionist being the equivalent term for terrorists in that post-Russian Revolution era.

So my question is this: Do we really know that any of these Tamil boat people are terrorists, as some—including Vic Toews, Canada’s minister of public safety—have suggested? Interestingly, Toews’ own forebears were accused of being “good revolutionists” as they fled to Paraguay after Canada closed its doors to them. Until proven otherwise, such statements are unhelpful and cause unwarranted animosity and unkind responses to be directed towards desperate people by normally generous and well-meaning Canadians.

Accusation 5

The Tamils evaded the normal process and had the audacity to come by boat!

Well, most Mennonites came by boat also. Indeed, some lived in refugee camps for a time first, the same as some of these Tamils. We, too, hired a boat to take us across the ocean. Fortunately, MCC made sure it was properly seaworthy.

Canadian culpability?

We need to seriously examine whether Canada bears some responsibility for the plight of these most recent Tamil refugees.

For many years, Canada sought to be an honest broker in overseas conflicts, recognizing that in most cases both sides commit indefensible acts and perhaps, at times, are also open to participate in doing some good. The goal should always be to try to inhibit the former and support the latter, which usually involves negotiating an end to hostility and seeking to broker a fair and equitable political solution.

Unfortunately, in recent years Canada’s approach appears to have changed. We now seem to be declaring one side “good” and the other “bad,” even when both bear culpability for hostilities.

So it was in Sri Lanka, where, several years ago, we declared one side “good” and the other “terrorist.” Usually, as in this situation, we chose the more powerful to be our ally and baptized them as “good.” The demonization of the other side as “terrorist” left Tamil civilians at the mercy of the more powerful, designated as a target despite the protections of the Geneva Conventions.

So did the tendency of recent Canadian foreign policy to choose sides contribute to the plight of the current boatload of Tamil refugees? It would seem so, and we must therefore ask whether we do not also bear additional responsibility for the predicament of these refugees.

Christian responsibility?

Does our Christian faith have anything to say about this? Of course, it does!

The oldest and most theologically significant biblical stories are about fleeing persecution and seeking refuge. The Israelite Exodus from Egypt was a 40-year refugee journey through the wilderness. Most theologians agree that this story became the theological paradigm for the New Testament story of salvation. Ours is a journey from captivity to liberty, from slavery to freedom.

According to the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus was a refugee who fled to Egypt with his parents. Not surprisingly then, Jesus indicated that a willingness to welcome the stranger was one of only a few key questions we will be asked “on the last day” (Matthew 25:31-46). Jesus’ entire ministry was deeply rooted in compassion, and he calls his followers to do likewise.

And Paul exhorts the church at Rome to “extend hospitality to strangers” (Romans 12:13). Similarly, the writer of Hebrews (13:2) expands on that: “Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it.”

Who knows? These Tamil refugees could be Canada’s angels come calling.

Edmund Pries teaches in the Department of Global Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ont., and is a member of W-K United Mennonite Church.

For a follow-up to this viewpoint, see “Mennonites and ‘Illegal’ Refugees Part II: Civil Law versus Divine Law.”

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.