As in many environments today, “peace” was a conventional salutation in the ancient world. In the Gospel of Luke, when the risen Jesus appears among the disciples in Jerusalem, he extends to them a greeting of peace.

This particular account of the resurrection reflects several themes specific to Luke’s gospel, and forms an important transition into Luke’s second volume, the Book of Acts. Some features of the narrative are highly memorable, such as the pair of sad characters who do not recognize the figure of Jesus as they trudge along, and Jesus’ insistence, when he appears to all of the disciples, that it is truly him, even eating some fish to convince the sceptics that he is not a ghost.

Luke portrays the disciples very positively, unlike Mark, and invests them with considerable power. The beginning of the chapter consists of the story of the women who had prepared spices and ointments for Christ’s body two days before, and who arrive at the tomb to discover that Jesus is gone. Two figures in dazzling white tell them that Jesus has risen, and the women return to the 11 disciples “and all the rest” (24:9) with this news. Yet the 11 do not believe the women, for “it seemed to them an idle tale” (24:11). Peter runs to the tomb and, finding it empty, returns home amazed.

In the next scene, two despondent followers, one of them named Cleopas, but the other unidentified, are walking along the road to the village of Emmaus and talking, when Jesus approaches them and asks them about what they are conversing. Surprised that he did not know about what had happened in Jerusalem, they speak of Jesus of Nazareth, and how he was a great prophet who was condemned, handed over and crucified. They then explain that they had hoped Jesus would redeem Israel, but that it had been three days since the execution. So far, no one had seen him (24:24).

In response to this, Jesus exclaims that they are “slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have declared!” (24:25) and goes on to analyze and interpret all the things about himself from the Scriptures.

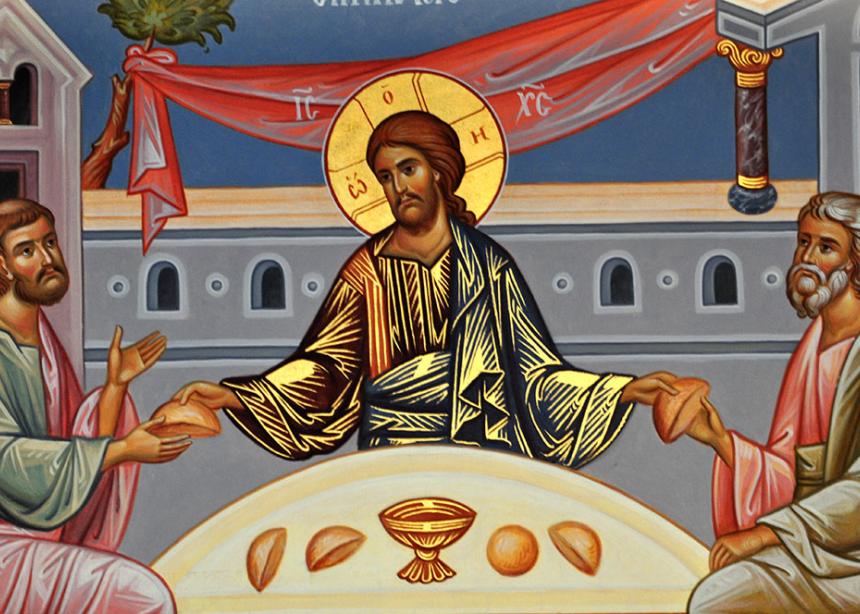

The two followers, still in the dark about who this stranger is, ask him to stay with them in Emmaus. There, at table, he takes bread, blesses it, breaks it and gives it to them. Suddenly their “eyes were opened” (24:31) and they recognize him, but he immediately vanishes.

The two return to the 11 disciples and their companions in Jerusalem, who were all gathered together. This latter group was discussing how Jesus had indeed risen and appeared to Simon (24:34). The two recent arrivals share what had happened and how Jesus’ identity “had been made known to them in the breaking of the bread” (24:35).

(To listen to “When He Broke the Bread”—words by Ross W. Muir / music by Sean O’Leary—see below.)

While they are talking, Jesus then appears in their midst declaring, “Peace be with you” (24:36). The group is terrified, but Jesus convinces them that it is indeed him, invites them to touch him, and eats a piece of broiled fish. He then explains that he is the fulfillment of prophecy and opens their minds to understand the Scriptures (24:45). He informs them that they must remain in Jerusalem until they have been “clothed with power from on high” (24:49).

Finally, Jesus leads them out to Bethany, lifts his hands and blesses them, and, while doing so, withdraws and is “carried up into heaven” (24:50). The final image in the gospel is of the disciples worshipping Jesus, then joyfully returning to Jerusalem, where they are “continually in the temple blessing God” (24:52).

Peace . . . and the breaking of bread

One of the themes evident in Luke 24 is the emphasis on meals and the breaking of bread. The fact that Jesus’ identity becomes apparent when he breaks bread with the two followers in Emmaus (24:31-32) both recalls the Last Supper, but also anticipates table fellowship as one of the important settings for life together among the people of “the way” in Acts (2:42, 46).

Whether these references have deliberate liturgical significance for Luke’s audience is difficult to say, but the author does emphasize that it is in this breaking of bread and sharing of a meal that Jesus is present among the believers.

These dimensions of the resurrection story are consistent with the gospel as a whole. In no other gospel does Jesus eat so often—indeed, he is accused of being a glutton and a drunkard in Luke 7:33-34—and with such a wide variety of people.

With whom one ate was very significant in the ancient world. Boundaries and hierarchies were maintained and reinforced by dining patterns. In Luke, Jesus breaks these boundaries by eating with tax collectors, Pharisees and sinners, and telling stories about banquets to which poor people, the blind and the lame are invited (14:21).

In Acts, after Peter has a vision of unclean foods, and hears a voice telling him to eat such foods (10:12-14), he states that, despite the prohibitions of Jews associating or eating with Gentiles, God has shown him that he should call no one profane or unclean (10:28). These verses illustrate that the practice of inclusive eating is upheld in Luke’s perception of the early church.

The message of “peace” mentioned above would not be an unusual way to address people in antiquity; it was both a typical means by which a Judean man could greet his friends and also a recurring theme in Luke’s gospel. In one of Peter’s speeches in Acts, he says that God’s message to Israel included “preaching peace by Jesus Christ” (10:36), and the church throughout Judea, Galilee and Samaria is also depicted as peaceful (Acts 9:31).

The meaning of “peace” could include a variety of dimensions, deriving as it does from both the Hebrew concept of shalom and the Greek notion of eirēnē. In some contexts, peace could simply mean the absence of war, but in other settings it had to do with material and physical health and accord among human beings. In Rabbinic tradition it often connoted notions of well-being and salvation. Jesus’ greeting of peace in Luke 24 may be understood similarly. Jesus offers an encouraging good wish for his followers, who must attempt to continue living in peace despite the fact that he will soon depart from them.

Jesus wishes people peace, but this does not mean that his followers will experience the rest of their days irenically. Members of the Jesus movement in Acts, such as Stephen, suffer and die for their deeds and words (7:54-60). Repeatedly throughout Acts, various figures within the church are killed, such as James the brother of John, who is executed at the orders of Herod Agrippa I (12:1-2). Others are tossed into prison, such as Peter (12:3). Paul and Silas are both stripped and beaten with rods before they are thrown into jail in Philippi (16:19-24).

Peace may be a characteristic of the church, but, according to Acts, those to whom the gospel is preached do not always receive it peacefully. Although the apostles try to be peaceful, they are often received with hostility. Acts ends with Paul under arrest, and does not say how Peter died, although some non-canonical texts contain accounts of their violent executions. Despite the message of peace, and the attempts to live in peace, there is no guarantee that one will have peace. In fact, seeking peace may invite persecution and death. If the church desired to create a culture of peace, but in doing so challenged the dominant values and practices of the day, it was not assured that its message would be welcomed.

Justice, liberation . . . and peace

A dimension of Jesus’ teaching and activity throughout the gospel of Luke is to proclaim justice and liberation through word and deed. Jesus proclaims the poor blessed, but also, as we have seen, eats with tax collectors and sinners. Some would appreciate such a message and activities, while others would react negatively to it.

Perhaps one of the reasons why Luke includes the greeting of peace by the risen Jesus to his followers is to offer a reminder that peace, in the gospel or throughout the Book of Acts, is not simply an absence of war, but the realization of God’s realm, in which all people can eat together, regardless of their social status or background, and those who are sick are healed. It is a deeper, more profound notion of peace that assures the well-being of everyone.

In a society in which all goods were perceived as limited, this meant that those who had more than they needed, such as wealth, would have to share

(Acts 2:44-45). Thus peace would require that some relinquish some of their possessions or sense of privilege. It would require that they share their table with prostitutes, sinners and outsiders. Peace, therefore, would not be welcomed by all.

Positive and negative peace

Peace is a central idea in many religions of the world, yet it obviously remains elusive, fraught as the world is with conflict. Those working in peace studies often point out that there are two concepts of peace:

- Negative peace is understood as an attempt to put a stop to violent conflict.

- Positive peace wants to minimize violence, but it focuses on issues of structural violence, which can occur in a variety of forms, such as economic injustice, sexism or environmental degradation.

A nation or community may not be experiencing violent military conflict internally or with another, but it still may be quite violent if there are all types of systemic social injustices. In such a context, some may experience this as peaceful because they enjoy a pleasant standard of living, while others, living in poverty, experience it as violent.

As a Central American peasant once pointed out in the New York Times, “I am for peace, but not peace with hunger.”

Positive peacemaking, therefore, would address the issues that create economic and social disparities. In doing so, it might upset the status quo and risk creating hostility among those who are more privileged, because positive peace requires structural social change. Peace in this sense is not simply the absence of war; it is the realization of a more just community. It is possible to end violent conflicts and achieve a negative peace without broaching the more profound underlying issues that prevent the possibility of ever attaining a deeper and more enduring positive peace.

The gift of peace Jesus offers

Despite the brutality that he had experienced, the risen Jesus extends peace to his followers, although they will soon face violence. I do not think that the story presents us with a Jesus who utters mere niceties, nor one who expresses a peace wish to a group, some of whom will soon face death, as a wry, ironic comment. Rather, Jesus offers encouragement to those who had become despondent: a gift of peace—positive peace—and hope that they must seek to sustain and share as they live in the world.

When thinking about gifts, John O’Donohue, the late Irish poet and philosopher, wrote in Eternal Echoes that “[n]o gift is ever given for your private use. . . . The gift calls you to embrace it, not to be afraid of it. The only way to honour the unmerited presence of the gift in your life is to attend to the gift; this is the most difficult path to walk. . . . It calls you to courage and humility. If you hear its voice in your heart, you simply have to follow it. Otherwise, your life could be dragged into the valley of disappointment. People who truly follow their gift find that it can often strip their lives and yet invest them with a sense of enrichment and fulfilment that nothing else could bring. Those who renege on or repress their gift are unwittingly sowing the seeds of regret.”

O’Donohue’s words cause me to think about Luke 24:36 as a free piece of encouragement—a gift —to continue seeking positive peace, even if at times it is seemingly impossible. In part, the purpose of the resurrection narratives is to bolster and legitimate Jesus’ followers, who are depressed about the demise of their leader and who wonder whether they should carry on. Jesus’ appearance, together with his message of peace and other teachings, motivates them, in turn, to use their gifts in order to persevere with their difficult work.

Passing the peace

In many Christian contexts there is a greeting of peace at some point in the worship or liturgy. How do people understand this wish for peace? One dimension of it that could be explored is this notion of the greeting as an impetus for people to continue to seek positive peace.

As O’Donohue says, our gifts are not given for private use, but to be shared with others, with the world. It is difficult, however, to sustain the courage, commitment and energy required to attend to the needs of the world in the face of setbacks. When we share the peace, it may be useful to think of it as a form of encouragement to pursue peace despite the hardships that such a path might entail. As such, “passing the peace” can be a concrete expression of hope.

The late Vaclav Havel famously stated in Disturbing the Peace that hope “is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out.”

Thinking about the “peace wish”—a gift and challenge from the risen Jesus—in light of these notions of sharing our gifts, positive peace, and in the context of the gospel and the story of the early church, may be useful, especially at this moment of renewed Easter hope.

Alicia J. Batten is an associate professor of religious studies and theological studies at Conrad Grebel University College, Waterloo, Ont.

For reflection and group discussion, go to the discussion questions related to this article.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.