There were two Lego sets and two groups of participants. The first group to assemble its toy would be the winner, but it quickly became apparent that the playing field was not level.

Group 1 made the rules, and the rules stated there was to be no talking and that the men in the group weren’t allowed to help construct the toy. In addition, Group 2 was not allowed to use the instruction manual.

The exercise was featured during a workshop hosted by the Micah Mission. Enitled “The awakening: Indigenous voices in restorative justice,” the two-day workshop was held in late March at the offices of Mennonite Central Committee Saskatchewan in Saskatoon.

The Micah Mission is an ecumenical organization offering restorative-justice programs to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals in Saskatoon. It is supported, in part, by Mennonite Church Saskatchewan.

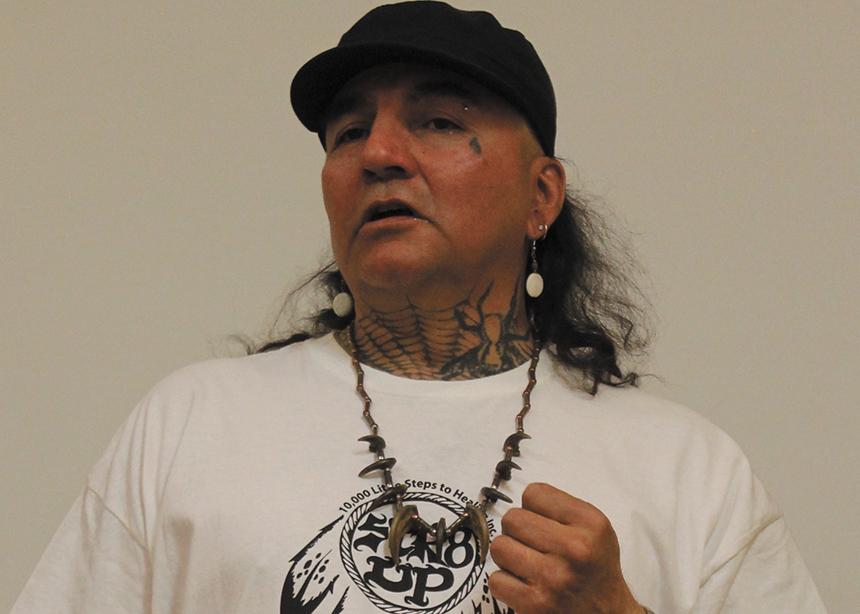

Hired in July 2018, Stacey Swampy is Micah’s Indigenous Awareness Program facilitator. As workshop emcee, Swampy shared his own story of more than 20 years in what he called “the system,” from growing up in foster care and group homes, to young offender care, to the adult correctional system.

He said he found healing in “going back to the teachings [of the elders], forgiving myself and cleaning my house up.” Now his long-term goal is to help others in the system.

Other workshop presenters from a variety of backgrounds offered insights into systemic racism, Indigenous life roles and loss of culture, to about 15 participants.

Becky Sasakamoose-Kuffner introduced the Lego exercise as part of her presentation: “Shifting the lens: From multiculturalism to antiracism.” A former policy analyst with the federal government, Sasakamoose-Kuffner now works as a race relations consultant for the City of Saskatoon. She introduced herself as part of the Sixties Scoop. Growing up, she was told that her birth parents selflessly relinquished custody of her so that she could be raised in a loving family.

When she met her Indigenous, biological father years later, she learned that this was not true. Her father’s family had wanted to raise her, but social services had taken her away and put her in foster care.

At the Truth and Reconciliation Commission national event held in Saskatoon in 2012, Sasakamoose-Kuffner shared her story. She also learned that her experience was not unique. “Tens of thousands of babies were removed from their families,” she said. “There was a lot of trauma. I realized that very kind, loving people could be part of a very racist system.”

While the Sixties Scoop may be a thing of the past, racism is not, she said. “We know racism continues to exist because the outcomes are so disparate between Indigenous and settler peoples,” she said. Saskatoon has become a city that does multiculturalism really well, she said, but multiculturalism doesn’t go far enough. “What are we doing to eliminate racism beyond going to Folkfest?” she asked.

“Race, according to original race theory, refers to categories and hierarchies that society has created to describe groups of humans mostly based on physical features,” she said. “The problem with this definition is the word ‘hierarchies.’ ” The difficulty lies not in the differences between people, but in the values placed on those differences, she said.

The Lego exercise was more than just a fun—or, for some, frustrating—activity. Sasakamoose-Kuffner told participants that the exercise mirrors what happened in the residential schools. The “no talking” rule was reminiscent of the rule in residential schools forbidding Indigenous children to speak their own languages.

The expected outcomes were the same for both groups in the Lego exercise, but Group 1 had instructions, while Group 2 didn’t. Similarly, in the residential schools, Indigenous students were expected to learn the same things in the same way as their settler counterparts, even though the ways of knowing and teaching were foreign to the Indigenous students, she said, adding that these were “societal constructs designed for some to succeed while others continued to struggle.”

In order to overcome racist structures, she said, “We must look at adopting an antiracist pedagogy.” But, she cautioned, “Indigenous people ought not to be responsible for eliminating racism. It ought to be institutions and organizations, top down, [implementing] actual concentrated and deliberate change of policies.”

History has shown that, “when policies changed, then attitudes and beliefs changed,” she said.

For Sasakamoose-Kuffner, it’s a matter of some urgency. “Racism isn’t politically or economically sustainable,” she said. “It’s imperative that we do something about it.”

It may be up to institutions and organizations to implement antiracist policies, but that doesn’t mean that individuals are powerless to effect change. “Inform yourself, stand up against racism, reflect, listen, share, believe, don’t be afraid to ask questions,” she concluded.

This article appears in the April 15, 2019 print issue, with the headline “Deconstructing racism.”

Stacey Swampy, the Micah Mission’s Indigenous Awareness Program facilitator, tells his story of life within the system and of healing, at a two-day workshop entitled, “The awakening: Indigenous voices in restorative justice.” (Photo by Donna Schulz)

Group 2 has all the advantages in assembling its Lego set, including the participation of the presenter’s 11-year-old daughter! (Photo by Donna Schulz)

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.