We all inhabit a genuinely complicated world—a world of generosity and incomprehensible inequality.

I have compiled various numbers and statistics that relate to the wealthy and the poor, and the efforts to bridge the divide—topics of interest to biblical writers.

Numbers, too, are complicated, and they are both informative and deceptive.

The wealthy

According to Forbes magazine, there were 2,755 billionaires in the world in 2021. This was 660 more than the year before. Of the world’s billionaires, 86 percent were richer in 2021 than the year before.

“Altogether the world’s wealthiest are [USD]$5 trillion richer than a year ago,” Forbes reported. That was a jump from an incomprehensible $8 trillion in combined wealth to an equally incomprehensible $13.1 trillion. For comparison, the U.S. government spent about $6.5 trillion in 2020.

Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, leads the pack with a net worth of USD$177 billion. Elon Musk is next at $151 billion.

Wealth is relative. While not in the “Bezosphere,” most of us are wealthy by global standards. Stats Canada says the “median after-tax income of Canadian families and unattached individuals was $62,900 in 2019.” That is incomprehensible to billions of peoples.

In 2020, the “median hourly wage for Canadian employees” was $25.50, up from $24.18 the year before. If paid over a full year of 40-hour work weeks, $25.50 per hour works out to a total of $53,040 before any deductions.

The poor

For reference, CNN Business calculates the “world’s annual average wage” at $20,328. This is adjusted for purchasing power in different regions. It means the equivalent of what USD$20,328 can buy in the U.S. Still incomprehensible to hundreds of millions.

The numbers are numbing, but the United Nations says that, pre-pandemic, about 700 million people—roughly 10 percent of the global population—were living below the global poverty line of USD$1.90 per day. The pandemic could push another 70 million into extreme poverty.

For comparison, according to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 35 percent of the world’s people lived in extreme poverty in 1990. In short, significant progress has been made, but there’s a long way to go. And COVID-19 has halted progress.

Official generosity

Government foreign aid—more specifically, Official Development Assistance (ODA)—is one dimension of poverty alleviation. In 1970, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a goal that would see “economically advanced” countries devote an amount equal to 0.7 percent of their gross national income to developing countries. Former Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson led a commission that recommended the 0.7 percent target.

Canada has never even reached 0.5 percent. For 2019-20, Canada’s ODA was just 0.31 percent of Gross National Income (GNI). On average, that percentage was higher when Stephen Harper was in power than under Justin Trudeau.

I asked Global Affairs Canada about the government’s position on attaining the long-standing goal of 0.7 percent. In a email, spokesperson Geneviève Tremblay noted various new and renewed funding commitments. With these, she said, “Canada remains in the Top 10 of OECD donors,” referring to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, an international body that serves as something of an umbrella for international aid efforts. Canada ranks 9th among OECD countries in terms of total amount of ODA in 2020 and 13th in terms of ODA to GNI percentage. Sweden and Norway lead that category.

While not mentioning the ODA-to-GNI proportion, Tremblay said, “The Government has committed to increase international development assistance each year to realize the 2030 agenda for sustainable development and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.”

The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim to “eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere” by 2030. The most challenging goals relate to inequality, climate, biodiversity loss, and “the increasing amount of waste from human activity.”

From trillions to millions

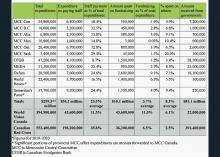

On a more relatable level, various faith-based organizations seek to address poverty. The charts below give a numerical snapshot of 13 Canadian organizations. I put the two biggest ones in their own chart. The numbers listed are publicly available on the Canada Revenue Agency website. Unless otherwise noted, figures are for 2020-21.

Numbers are limited in what they can communicate, as are short promo articles about poor kids holding cute goats. The numbers in this article are either big or small, depending on where you sit. Those who like charts will draw their own conclusions. As they should. Those who don’t like charts will turn the page. As they should. Some administrators will surely want to add explanations.

It’s all complicated. Just like all of our lives. Part of our responsibility is to dive into the complexity and grapple with it.

Comments

A statistical look at global wealth and poverty may have its usefulness however it then needs to be made clear as to how this could be useful. I used to teach middle-years English Language Arts (not very well, mind you), including writing. One of the criteria of a piece of writing was that it needed to answer the question "so what?" or "what makes this response/information so important?" Or put another way, "what should the average Canadian Mennonite reader do with this information?"

As dry statistical information, a look at global wealth and poverty remains at arms length, distant, without impacting the reader, it is information the Canadian Mennonite reader is already generally aware of, at least the inequities of wealth accumulation. I question what it is that I should do with this already familiar information?

Back in the day when I was still a regular church attendee and member of my local General Conference of Canada Church, our church like many of its day, suffered from significant budget shortfalls. At the time, I was employed in the local credit union, the financial facility where most of our church members had their accounts. I knew basically how much money was available to most members (generally a lot). At our church annual meeting I suggested we all make our annual tax returns public and available to the church in order to see where the financial problems might be and if they were legitimate. After (to my recollection) some moments of stunned silence, an uproar ensued. How dare I suggest ... Needless to say the church annual budget was just barely met one more time, paid for by those who contributed above and beyond.

I think only God knows how much money Mennonites have, not even Will Braun knows, but there used to be a lot of it.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.