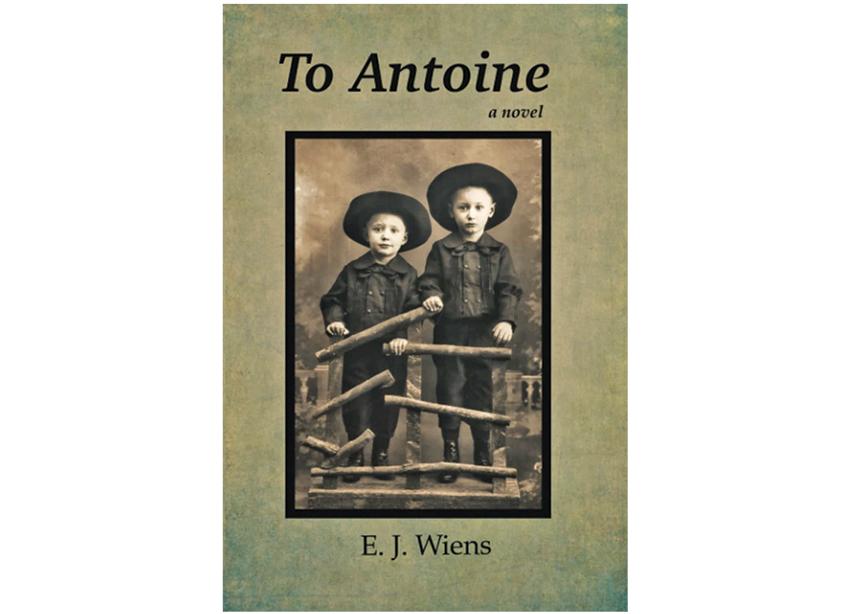

E.J. Wiens has written a powerful story that explores the question of Mennonite collaboration with the Nazis during the Second World War. Hesets this question within the broader context of Mennonite history and helps the reader to understand the nuances and moral discrepancies faced by Mennonites who fled Russia (present-day Ukraine) in 1943. The book also raises other questions, including whether Mennonite churches in Canada have been guilty of harbouring war criminals.

To Antoine is written as a series of letters by an elderly Mennonite living in Canada, to someone he knew in his childhood and as a young adult. Through these letters, set in the early 1990s, Peter Enns reflects on his life and his experiences before, during and after the war.

Normally I do not find novels written in this letter format to be inspiring, but in this book it works. I found myself so caught up in the story that I often forgot I was reading a supposed letter. Wiens’s writing style is compelling, and his characters are convincing.

In an online interview with the publisher, Wiens says he chose this style so that he could write in the first person, but also make the narrator “cantankerous.” He wanted the narrator to be honest and critical with himself and his community, so that the reader can be continu- ously challenged.

“I wanted the structure to allow the narrator to argue with someone he respects but also has some reservations about,” says Wiens. “This puts pressure on the narrator not to lie.”

Antoine, to whom the letters are written, is not a Mennonite but was very well known to the narrator in his childhood and then in Berlin immediately after the war. The reader is kept in suspense throughout the novel, wondering exactly what happened in Berlin to explain the friendly but cautious attitude of the letters. The puzzle of Antoine is a hook, keeping the reader engaged.

As Peter Enns sits on his park bench in Winnipeg, reflecting on his life, he describes the 1930s to 1950s as “[a] time when all the moral compasses spun crazily in their binnacles [a built-in housing for a ship’s compass], when the coordinates of good and evil were tossed about in a swirl of rival manias.” He suggests that it was a bit of a miracle that anyone survived, as they were “caught between the Soviet hammer and the four-pronged hook, the chaff between two millstones.”

These words are written near the beginning in a kind of introduction. Most of the novel is written in much simpler language, often with dialogue. Wiens scatters German words throughout, but not in a way that makes it unclear.

The general outline of the story is not surprising for anyone familiar with this part of Mennonite history. The narrator leaves his homeland as the Germans retreat. He joins the German army toward the end of the war but, when everything is over, he finds himself among millions of other refugees trying to escape from the Soviet army. After many adventures he settles in Paraguay with help from Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) and later moves to Canada.

Very little in this story is morally simple. Even the role of Peter Dyck and MCC in helping refugees after the war is seen from an unusual perspective. The question of “who is a Mennonite” becomes very muddy in this context.

I smiled when I read the final paragraph in which the narrator overhears an amusing conversation. Wiens concludes his book with the hint that no one should judge the actions of an earlier generation without understanding their history.

To Antoine is published by Gelassenheit Publications, a project of Jonathan Seiling of St. Catharines, Ont., that aims to publish works in the Anabaptist-Mennonite tradition. This book is available at commonword.ca.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.