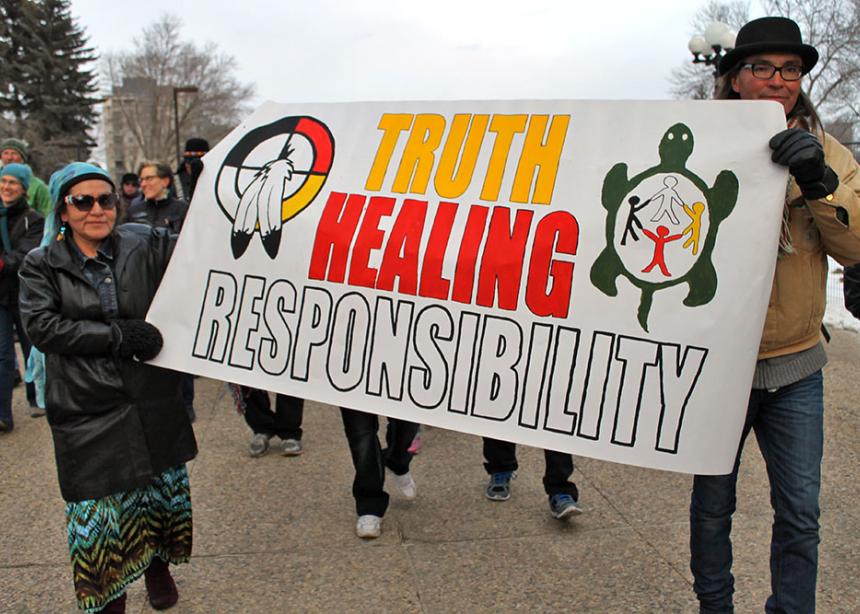

I was standing beside Neill Von Gunten, former co-director of Mennonite Church Canada Native Ministries, and trying to peer over heads to see into the “Churches Listening Area” at the final Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) national event in Edmonton last month. An aboriginal leader had just prayed, and a church leader suggested a song; “We are Marching in the Light of God.”

As the first notes sounded, an indigenous man pushed past us and left the area. “That man just walked away saying I’ve had enough of that,” Von Gunten explained. “For us, it may be meaningful, but for some survivors it brings up hard memories. They sang some of these songs in residential school.”

Indian Residential Schools have left a painful and crippling legacy; tore families apart; and subjected thousands of children to abuse, desperate loneliness, hunger and disease, and separation from all aspects of their cultural heritage.

Like the six events before it, the one in Edmonton encouraged survivors to record or tell their stories, providing a place for the telling of Canada’s shameful and hidden history of residential schools.

From 1870 to 1996, more than 150,000 indigenous children were placed in the federally funded, church-run institutions. In 1907, Dr. P.H. Bryce was sent to evaluate health conditions in residential schools. His report called the situation at schools a “national crime,” with unacceptable levels of student deaths occurring. Death rates of 24 percent were common. At the File Hills First Nation in Saskatchewan, 75 percent of the students died in the first 16 years of the school’s operation. Shockingly, Bryce’s recommendations were suppressed and largely ignored.

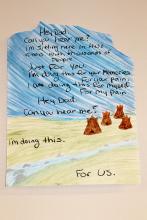

The words “For the child taken, and the parent left behind” were emblazoned everywhere in the TRC venue, and it was poignantly clear that damage to indigenous people is intergenerational and ongoing. Dysfunctions resulting from trauma and loss are handed down through families, continuing to wound even though the schools are gone.

Survivor after survivor came forward to tell their stories in sharing circles. Many wept, saying they were unable to be good parents to their own children. Many spoke of alcohol as an escape from memories and nightmares, an escape that only adds to the hurt.

While the telling of truth may be a first step in reconciliation, it is immensely painful in itself. One survivor spoke about being put in a residential school as a small child and not being allowed to speak his language at all. “For the first three years, I didn’t know what was said or what was going on,” he said. “It was mass confusion.”

A survivor from the Onion Lake Residential School told the sharing circle: “Being here at this conference has a lot of triggers for me. Listening to Christians, I heard Christians say they loved these children. . . . If that’s your definition of love, that’s not mine!”

At an interfaith panel discussion on reconciliation, panelist Leona Makokis of the Saddle Lake Cree Nation told some of her story. “Speaking my truth is not intended to hurt anybody, but to remain kind,” she said. “We cannot reconcile unless we know the truth of what happened in Canada.”

She believes that people of all races and faiths must work together for reconciliation. “People are very well intended, but because they lack the knowledge, the whole colonial process continues,” she said.

Roger Epp, who wrote “What is the settler problem?” column for Canadian Mennonite (Sept. 2, 2013, page 23), was a Mennonite representative on the panel. He said that Christians need to un-tame the Good Samaritan story and tell it again. “It powerfully undercuts all the powerful hierarchies we carry in our heads,” he said. “The first step outside the settler mythology is to be a neighbour.”

The road to healing and wholeness is long for residential school survivors and their descendants. While attendees heard many painful stories, there were also sto-ries of hope and healing. Often in their speaking, survivors celebrated years of sobriety, spoke of reconnecting with their native language and culture, talked of the process of discovering and improving family relationships, and, above all, they spoke of connecting with the Creator as a critical element of healing.

What’s next?

The national events are now over. As hard as it was for people to tell and hear the awful truths of residential school survivors, TRC attendees were told the process is going to become even harder.

During the closing ceremonies Justice Murray Sinclair was hopeful but blunt in his concluding remarks: “The truth will set us free, but first it’s going to piss you off. . . . If you think the truth was hard, reconciliation will be even harder.”

Sinclair has a very good point. The seven national TRC events provided a structured way for indigenous people to have their stories recorded and heard. It gave settler peoples a place to hear and learn. But now what?

Once the truth has been told and the structure for hearing it is gone, what happens? On March 30, Mayor Don Iveson proclaimed a year of reconciliation in Edmonton, announcing three specific initiatives the city will enact. These include aboriginal youth leadership initiatives, an education program for city staff to work at reconciliation in the workplace, and cooperation with aboriginal communities to create a venue for spiritual and cultural reconnection and celebration.

—Posted April 23, 2014

For more on Mennonites and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, see:

Anabaptist church leaders offer statement to residential school survivors

A modest proposal for truth, reconciliation

‘A foolish act of love’

Poem: Truth and reconciliation

‘Four directional thinking’ on indigenous-settler relations

American Mennonites attended past TRC event

One thing lacking (sermon)

Who is blind? (sermon)

Truth and reconciliation is ‘sacred work’

Day schools issue hits home

Comments

Thank you for this article and for sharing a piece of the experience and the knowledge of truth with those who were not there at the national events.

I wanted to let you and your readers know that the mandate of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has been extended for one year. There will be an event - a national gathering - to receive and carry forward the final report. The details of just what that will look like are yet to be determined, but we know it will be in Ottawa in June of 2015. KAIROS will be involved so you can check our website (www.kairoscanada.org) or contact us for more information in the months to come. Hope to see you there.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.