“There’s a crack in everything / that’s how the light gets in,” is often quoted by Christians as hope that God will “get in” to any situation. But the quote has a strange source, penned and sung as it was by Canada’s own beat poet, Leonard Cohen, that Jewish? Christian? Buddhist? lady’s man, from the song “Anthem” on his 1992 album The Future, which contains references to drug use and sex acts. Leonard Cohen: Is he a saint or sinner?

I was at a meeting of Mennonite Church Canada leaders on Nov. 7 last year when one of them leaned over with his cell phone and showed me, “Leonard Cohen, dead at age 82.” “Have you got his last CD?” he asked.

I replied that I didn’t yet, having it on my Christmas gift list so that my children could give it to me if they wanted. “You’ve got to get it,” he said. “It’s his best yet.”

We then entered into a conversation about his last few discs, including Common Problems, which won the 2015 Juno Award for Album of the Year. I noted that the last two songs of that album, “Born in Chains” and “You’ve Got Me Singing (The Hallelujah Hymn),” seemed to me to be Cohen making his peace with God, returning to his Mosaic faith, on the one hand, and hoping in the One to whom hallelujahs are addressed, on the other. The leader agreed.

Cohen has always given me a mixed set of feelings. It seemed that every time he released a new album over the past 25 years, there was a different woman on his arm, and there were a string of women in his past. Could a womanizer like him have profound things to say to me and other Christians? In later years, he seemed to have gotten his drinking under control, perhaps at the same time he had come to terms with clinical depression at the Mt. Baldy Zen Center in Los Angeles, Calif., where he went in 1994 and was ordained as a Buddhist monk in 1996.

But then there were the lyrics whose sources came from Christian and Jewish themes and stories, even his much-sung “Hallelujah” (Various Positions, 1984). He seemed to straddle the holy and profane easily.

In “Going Home,” the lead song on his 2012 Old Ideas album, he names that chasm, with God speaking: “I love to speak with Leonard / He’s a sportsman and a shepherd / He’s a lazy bastard / Living in a suit / But he does say what I tell him / Even though it isn’t welcome / He just doesn’t have the freedom to refuse / He will speak these words of wisdom / Like a sage, a man of vision / Though he knows he’s really nothing / But the brief elaboration of a tube.”

The refrain has Leonard responding: “Going home / Without my sorrow / Going home / Sometime tomorrow / Going home / To where it’s better / Than before.”

Naming himself as both “lazy bastard” and “a sage, a man of vision,” seems to describe him, perhaps referencing David, the “sportsman and shepherd” of Cohen’s Jewish background.

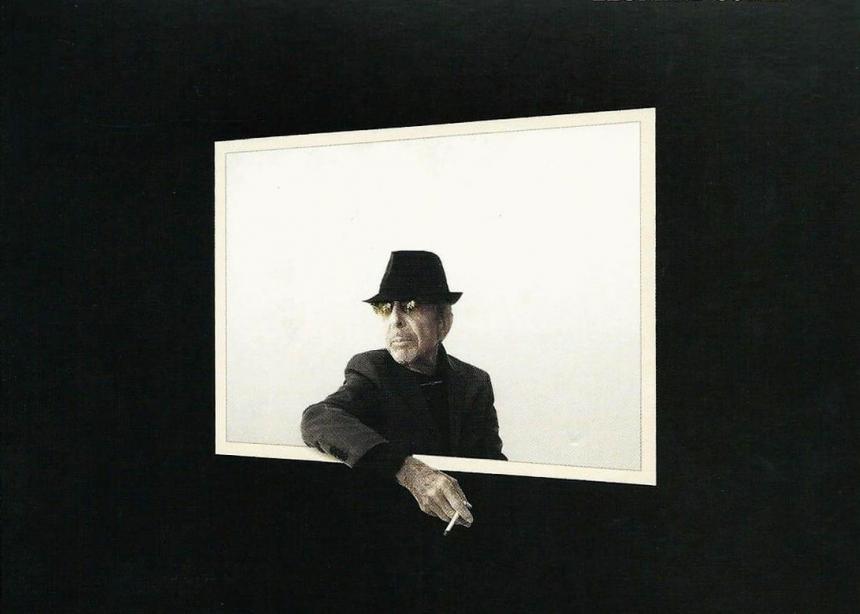

He seemed at peace with this—until his final album before his death: You Want It Darker. Suffering from “severe back injuries and other disagreeable visitations,” he and his long-time collaborator, Patrick Leonard, who also suffers similar conditions, had given up on the album until Cohen’s son Adam came and helped him produce it. You Want It Darker has God demanding suffering while dealing out rejection.

In “Treaty,” the second song that is reprised at the end of the album, Cohen sings, “I wish there was a treaty we could sign / between your love and mine.” These last words to his public on record seem fatalistic and final, suggesting that his carnal life and God’s spiritual love cannot be bridged. There is no “treaty,” no covenant.

As many writers have noted, this felt like a final album, a goodbye much like David Bowie’s Black Star, released days before his death in early 2016. Faced with his inevitable death, in pain and grief, did Cohen begin to wonder about his eternal future? Did his life of immoral choices begin to suggest that he did not have a future with God? Or did he still wonder? Backed by a Jewish cantor choir and soloist, he also sang, “Hineni Hineni, I’m ready, my Lord.”

In spite of God’s coming judgment and the suffering of people all over the world—and perhaps more particularly the innocents who suffer in so many of his songs—he was ready to put himself into God’s hands, whatever the outcome. Not resting on any laurels or claiming any rights, he seemed to depend on grace.

Not a bad role model to follow.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.