Only in the last decade has the extent of Canada’s mistreatment of its Indigenous peoples been widely recognized. The most horrific example of this mistreatment was the residential school system that saw 150,000 Indigenous children taken from their families in an attempt to forcibly assimilate them into white Christian culture by driving out Indigenous languages, spirituality and cultural traditions. While this tragic story has been told in a few documentaries, there have been few attempts to relate it through the medium of narrative film.

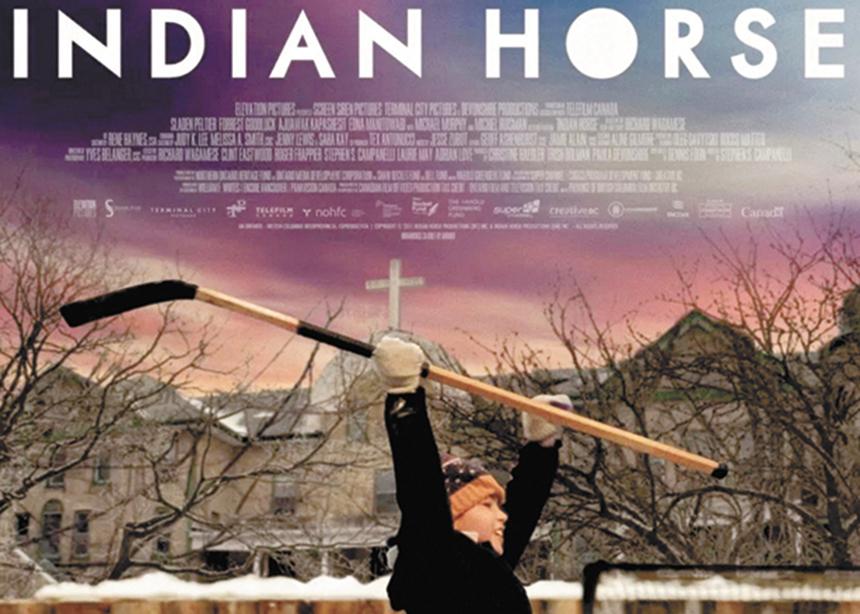

The recently released Indian Horse, directed by Stephen Campanelli, not only corrects that lack but does so with a power and urgency that few Canadian films have achieved. Based on the 2012 novel by Richard Wagamese, who died last year, Indian Horse tells the story of Saul Indian Horse, an Ojibwe boy in Northern Ontario, from age six in 1959 through early adulthood in the late 1970s.

Despite his grandmother’s desperate attempt to hide him from the authorities, the young Saul is caught and forced into a Catholic residential school. There, Saul (played by Sladen Peltier) experiences and witnesses the kind of cruel, abusive behaviour from teachers (in this case nuns) that led many students to take their own lives. One particularly heinous method of discipline is a small cage in the dark, dank basement of the school. But Saul connects to one of the priests, Father Gaston (Michael Huisman), who takes an interest in him and introduces him to hockey (on TV).

Practising on his own in the early mornings, with frozen horse droppings for pucks and borrowed skates that are much too big for him, young Saul quickly masters the sport, which becomes not only an escape from the school’s cruelties but the focus of his life’s path.

As a teen (Forrest Goodluck), Saul is invited by the coach of a small-town Indigenous team (Michael Lawrenchuk) to live with his family and play for his team. Father Quinney (Michael Murphy), the school’s principal, reluctantly allows Saul to leave. Saul flourishes in his new loving home but he also experiences the racism of white players and white townspeople, reminding him of his past.

Still playing well as a young adult, Saul (Ajuawak Kapashesit) comes to the attention of an NHL recruiter (Martin Donovan) and begins playing for the Toronto Monarchs, where he finds yet another form of racism. This will be the final straw, leading to an ending that makes it clear we are not watching a sports film.

Indian Horse features spectacular cinematography and some fine acting. Peltier and Goodluck stand out in particular as the younger Saul. The screenplay is generally well written, although the twist at the end is a questionable choice. The direction and acting are occasionally uneven, but Indian Horse is an admirable effort for a small Canadian film.

In the end, however, it’s not the quality of the film but its story, that is of utmost importance. It’s a story that every Canadian needs to know because, in spite of the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we have been blind to our racism for far too long and need the power of narrative film to help open our eyes.

Racism and the mistreatment of Canada’s Indigenous peoples did not end with the last residential school in 1996. It remains Canada’s hidden shame, as witnessed in the struggles on our reserves to have clean drinking water and adequate housing, in the slow response to missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, and in our country’s ongoing efforts to extract resources from Indigenous lands without consent.

During the last century, Mennonites in Canada have often been complicit in this racism—I, for one, grew up with racist attitudes toward Indigenous people in Winnipeg—even as some of our leaders led the way in promoting a better understanding of, and respect for, our Indigenous neighbours. This is surely the path that Jesus calls us to take.

So I am not just recommending Indian Horse, but suggesting it is the responsibility of every Canadian to watch this groundbreaking film. Don’t be scared off by the 14A rating. The film deals with adult themes, but there is no graphic violence, sex or language.

Comments

Although the movie Indian Horse was worth watching and is fairly faithful to the book by Richard Wagamese, I would encourage people to read the book before seeing the movie. Wagamese is a master storyteller and a beautiful writer. His book Indian Horse is a classic, and I consider it one of the finest Canadian novels I have read. The movie version pales in comparison. Indian Horse was a popular addition to the Indigenous relations section of the library at my church, and I encourage other churches to purchase a copy as well.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.