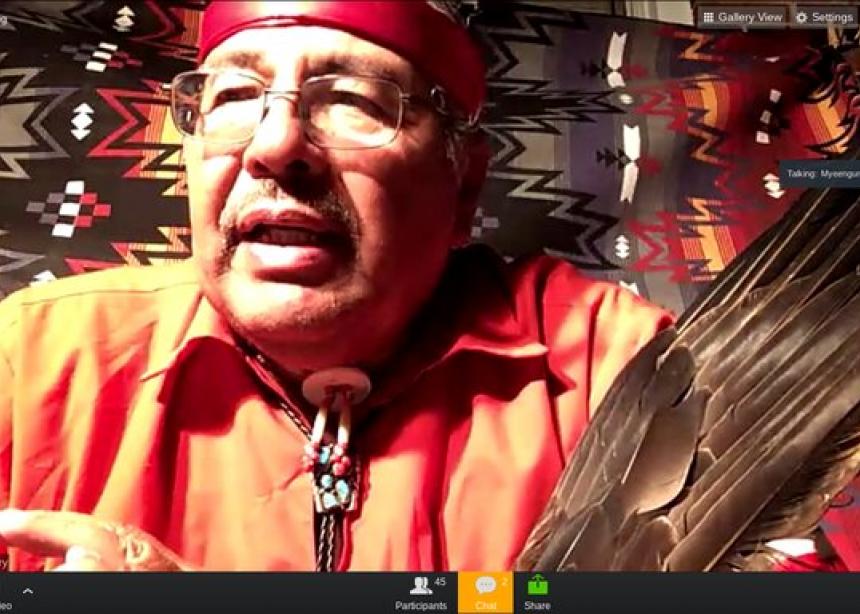

Myeengun Henry, Indigenous elder, says treaty relationships should be tended. “We need to shine those up every year so we don’t forget how important they are.” Henry was the first speaker in a seven-month, online storytelling series called “Treaty as Sacred Covenant: Stories of Indigenous-Mennonite Relations,” that centres on covenants made, broken and renewed.

A former chief of the Chippewas of the Thames, Henry teaches and provides Indigenous services at Conestoga College, Kitchener, Ont., through a program called Be-Dah-Bin Gamik.

As part of the storytelling series sponsored by the Truth and Reconciliation Working Group of Mennonite Church Eastern Canada, this session explored what happened to treaties made generations ago between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. He insists “those treaties still exist” and “we can honour those treaties today.” We can find ways to “live jointly on the land in ways that [don’t] infringe on each other. . .we can co-exist and live side by side.”

The working group was formed in response to the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) final report and calls to action, some of which were addressed to churches and faith groups. This online storytelling series will include Indigenous and Mennonite non-Indigenous voices, “shining light on the history of broken covenants [and] illuminating pathways of hope to a more just future for all nations on this land.” According to the description of the series on MC Eastern Canada’s website, “broken treaties with Indigenous peoples will continue to fuel Indigenous-Settler conflict unless we learn from history.”

The first event was facilitated by Josie Winterfeld, who is part of the working group. More than 100 people joined to hear Henry’s presentation. He described how over 500 years the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples swung “from partnership to paternalism” driven by a government-directed process of assimilation. He traced several stages in that relationship.

The relationship began with Indigenous partners assisting early settlers with survival skills like how to build shelters and find food and medicine. Alliances formed and nation-to-nation treaties were signed for “as long as the sun shines, the grass grows and the river flows.” But there were fundamental differences in how people perceived the land and the treaty-making process. Henry said that for Indigenous people, treaty-making was done in a “spiritual manner.” Treaties were depicted in wampum belts—visual representations of the story of that sacred covenant.

Caring for the land was also “a spiritual activity.” Indigenous people used the land but kept it pristine, Henry said. By contrast, settlers saw the land as empty and unused. For them land and its resources were there to be claimed, designated and used. Indigenous people “were getting in the way” of those aims, so governments established reserves and residential schools to deal with the “problem.” This “act of displacing” Indigenous people caused leaders such as Pontiac and Tecumseh to try to protect their way of life, but the “power tilted” to non-Indigenous people. “We were not dying fast enough,” Myeengun said.

He described the residential school system as “the worst thing that could happen.” Losing language, culture and ceremonies “devastated the population” leaving a legacy of anger, poverty and hurt that is still “moving through generations,” he says.

Henry says “we don’t look back far enough to see how or why” Indigenous resistance and confrontations are happening today. He describes broken relationships and treaties as “the ghost of our history.” It was vital that everyone live up to those treaties. When that gets neglected “we are willing to stand up.” He sees the present relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples as one of “recovery, reconciliation, renewal and renegotiation.”

After Henry’s presentation there was an opportunity for questions and interactions. One person asked about the church’s response to climate change. Henry’s reply was “the land is our mother. We need to protect her.”

The next storytelling event scheduled for Oct. 20, 2020, features Janis Monture from Six Nations of the Grand River, Mohawk Nation Turtle Clan, who is executive director of the Woodland Cultural Centre.

People can register for individual sessions or take in all of them. Each storytelling event will be recorded. Visit mcec.ca/programs/truth-and-reconciliation for details.

Do you have a story idea about Mennonites in Eastern Canada? Send it to Janet Bauman at ec@canadianmennonite.org.

Related story:

Evangelical path to truth and reconciliation

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.