Transformative. That’s the word Cheryl Woelk uses to describe the impact of language teaching and learning on human relationships.

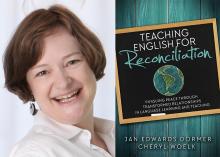

She recently co-authored a book on the subject, together with Jan Edwards Dormer. Teaching English for Reconciliation: Pursuing Peace through Transformed Relationships in Language Learning and Teaching offers insights into using the English language-learning environment to build peace.

Woelk, who hails from Saskatchewan, is a language teacher and peace educator. Based currently in Seoul, South Korea, she coordinates the Language for Peace project, which is sponsored by Mennonite Partners in China. She’s also a consultant with Collective Joy, a peacebuilding initiative that offers conflict resolution workshops to organizations and educational institutions.

Dormer is a professor of TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) at Messiah College in Pennsylvania. Having taught in other cultural contexts, she developed an interest in using language teaching for peacebuilding.

In 2015, Dormer attended a Christian English-language teachers’ conference in Toronto, at which Woelk was a presenter. The two connected and decided to collaborate on a book that would be a resource for English as a Second Language (ESL) teachers.

Language teaching is much more than a means to an end, says Woelk. “It touches on every aspect of a person’s life. It is a new way of relating and a new way of understanding conflict and conflict resolution,” she says, adding, “It’s a space we create together.”

It is a space that has to do with relationships and how those relationships are nurtured. “In ESL, the content is set, but we can use a peacebuilding lens to frame the content,” says Woelk.

In their book, Woelk and Dormer explore how teaching methods can enable peacebuilding. One such method might be allowing marginalized voices to be heard in the classroom.

They also consider how different skills can foster peacebuilding. “So [many] peacebuilding skills have to do with communication,” says Woelk. To encourage learners to hear one another, for instance, one might teach the skill of active listening.

In discussing educational systems, the authors stress the importance of being aware of the larger context. “A class of refugees from all different countries is very different than a class of business executives in Korea,” says Woelk. “It’s important to be aware of who you’re teaching and why the class is happening.”

Woelk feels her own experience of learning Korean has made her a better peacebuilder. “Early in my time in Korea, I had a conflict with a colleague about washing dishes,” she says. “I thought I had learned to speak respectfully, but [my colleague] was very hurt by what I said.” The words she chose were more powerful than she realized, but because her colleague was willing to talk with her about it, Woelk learned better ways to express herself in her new language. She also learned much about the power of language in conflict situations.

Woelk has also seen language learning transform her students’ relationships. She once taught a refugee resettlement class with students from two or three different backgrounds. “At the beginning there was distrust and hesitation to engage. They didn’t know each other and didn’t know if they should,” she says.

But as they began using their very simple English, relationships started to form. “The class became a source of coherence for them, and their resistance started to dissipate,” says Woelk. “If we had followed the textbook, [the language] would have been only transactional, but we brought in relational language as well.”

On another occasion, Woelk taught English to a group of Korean business workers, all from the same office. “It was a little awkward because the boss was at the lowest level of proficiency and his secretary was at the highest,” she says. “In their own language they would never have spoken on an equal level, but over the course of several months, these two changed their way of communicating, and the boss became able to listen more openly to his secretary.”

Occasionally peacebuilding happens more overtly. Woelk once taught a group of young people from both North and South Korea. As students discussed peace and conflict resolution, “everybody’s understanding of peace shifted,” she says. “Peace is not something we have a common definition for.” The class challenged students’ stereotypes, as they came to realize that peace for one side might not necessarily be peace for the other. Woelk says this experience also transformed her as a teacher.

Dormer and Woelk hope their book will be an easy-to-read resource for ESL teachers. While their Christian perspective is woven throughout, they also hope its teachings will be applicable to readers from non-Christian perspectives.

To learn more, visit language4peace.org/.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.