Mennonite Central Committee Ontario (MCCO) has announced the June closure of the Circles of Support and Accountability (CoSA) programs in Hamilton, Toronto and Kitchener, as well as the Faith Community Reintegration Initiative. The programs supported people coming out of incarceration.

An MCCO release states that “sustainable funding from both federal and provincial governments has remained elusive.” Other sources of funding have likewise been difficult to secure, making continuation of the program “untenable.”

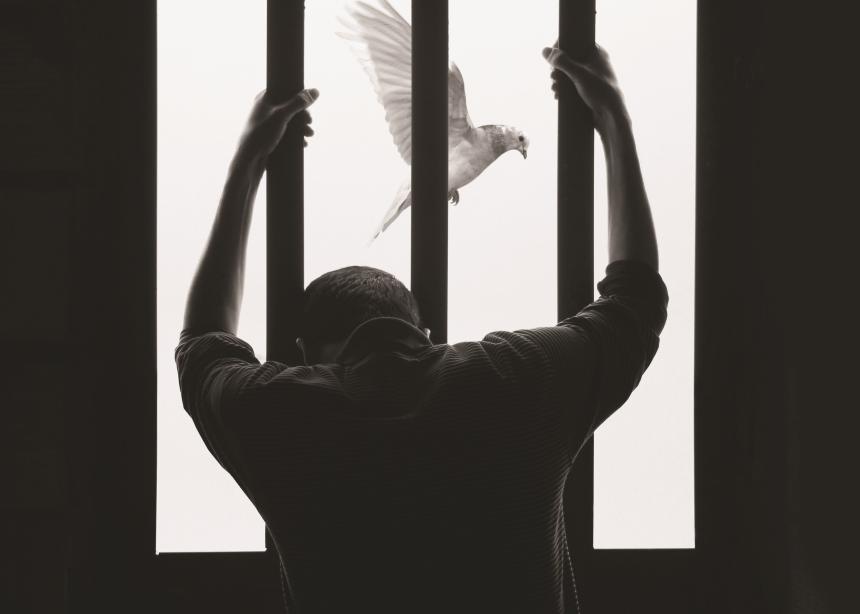

Thirty years ago, Mennonite pastor Harry Nigh of Hamilton was asked if he could find a place for a sex offender to reintegrate into society when released from prison. Out of that request CoSA began; a program where volunteers “circle” and support a “core member” following their release from prison. Most often these are sexual offenders.

Nigh, now retired but still connected with CoSA, called CoSA “true to our grassroots peacemaking” as Mennonites. Speaking by phone from his home, Nigh said, “it’s intrinsic to the basis of MCC.” He sees Mennonites “stepping into situations that are grey and chaotic,” and “[seeing] the humanity of the people we work with.”

CoSA Canada provides an umbrella for 15 CoSA programs across the country, including the three MCCO CoSA programs. In an interview, Eileen Henderson, who serves as chair of the CoSA Canada board, said the closure of the MCCO programs has been devastating for the roughly 40 core members concerned and people on the waiting lists.

“The people on the waiting list aren’t even in limbo,” said Henderson. “They’ve just been told what they thought they had, has been taken away.”

Executive director of CoSA Canada Cliff Yumansky said CoSA needs a mix of government, private and church funding. To sustain circles across the country, community-based funding is needed. Ideally, he said, government would pay CoSA a sum for each core member, with church and community supplementing the rest. He suggested some pressure could be put on Members of Parliament to encourage Correctional Services to participate more sustainably.

The search for funding has been a significant focus for staff across CoSA programs, most of whom are part-time or volunteers. “It stretches us thin,” Yumansky said. He says that time and energy should be spent on core members.

While CoSA began in Hamilton, it has been replicated across Canada, the U.S., Britain, Australia and South Korea.

CoSA has shown a significant success rate. A 2018 study in Minnesota found that sex offenders who go through the CoSA program are 88 percent less likely to reoffend than those not in the program.

Canadian Mennonite asked Correctional Service Canada (CSC) how they plan to safely reintegrate sexual offenders into society without CoSA. In an email, a spokesperson said, “CSC remains committed to managing sexual offenders in an appropriate manner…. As a part of the consistent continuum of care throughout the correctional process from intake up until release into the community, CSC provides correctional follow-up services to offenders.”

Canadian Mennonite also reached out to Public Safety Canada regarding CoSA funding but did not receive a reply.

With the announcement of the closure, MCCO stated it “will work closely with community partners to support individuals in finding alternative support programs in the community.” At the same time, MCCO acknowledges this “will present challenges, as these programs offer something unique and irreplaceable.”

Henderson and Yumansky say there are no alternative programs in the community.

Sheryl Bruggeling, who speaks for MCCO, said that while the organization has explored many options, “there are no revenue options available through government grants and contributions programs for this work in Ontario at this time.”

Bruggeling said MCCO’s “overall revenue remains stable,” and, other than CoSA, “no other MCCO programs are facing reductions.”

The last government funding CoSA received was a five-year contract ending in 2022. During that time, Public Safety Canada funded approximately 53 percent of the overall program budget. Since that time, MCCO has shouldered the funding burden, while seeking other funding sources.

Three CoSA staff members will be laid off as a result of the closure.

When asked if they think MCC offices in other provinces will follow MCCO, Henderson and Yumansky weren’t sure, but Henderson noted that MCC Alberta recently made “a definitive choice” to move ahead with their CoSA programming.

CoSA staff have been hearing words like “discarded,” “betrayed” and “abandoned” from core members and folks on the waiting lists. These sentiments “escalate risk” of reoffending, said Henderson. She quoted one staff member who said, “it feels like things are just being thrown away.”

Yumansky said the board of CoSA Canada is working hard to find ways to keep the work going in the areas where MCCO was operating. “We feel encouraged about some of the conversations we’re having.”

“Rebuilding of hope and trust with core members will be challenging. We have to convince them that what has just happened won’t happen again,” said Henderson.

All current CoSA programs outside of Ontario are continuing, as well as programs in Ottawa and Peterborough, Ontario, which operate independent of MCCO. A few circles across Canada are operated exclusively by volunteers.

David Byrne is a former chair of CoSA Canada and has recently completed his doctoral research on the theology and history of CoSA. Byrne said the importance of these particular CoSAs in central Ontario cannot be overstated. Many people being released from prison settle in the Toronto, Hamilton and Kitchener areas.

The number one predictor of reoffence in sexual offenders is relationships, said Byrne. Without these circles of support, community safety is at risk.

The process of offending and going through the justice system is dehumanizing. Offenders feel very disconnected from whatever community they re-enter. Byrne said “CoSA turns that on its head” with its “counter-intuitive response” of embracing the former offender. “In building that relationship there is a reinvestment in the community.”

“I get why that’s hard to fundraise for,” said Byrne. “CoSA is a remarkable Canadian success story, but in a lot of Canada we haven’t done a good job of creating CoSA practitioners in the next generation.”

Very few sexual offenders are sentenced to life in prison, and almost all of them will be released at some point. CoSA’s relationship-building positively affects the community in ways that aren’t easy to notice.

“There are literally hundreds of kids and people who have not suffered trauma and abuse because of this program,” Nigh said. “What about the kids? Who steps in there?”

Nigh said CoSA is a tough sell; very few people are excited about the idea of supporting sex offenders. But it’s “essential that we look at some form of continuation.”

He doesn’t believe MCCO wanted to make this move; they were simply left with no choice. He has hope, though. Ottawa and Peterborough CoSAs remain open. “It was a very grassroots thing [in the beginning], so why can’t that happen again?”

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.