More than 12,500 refugees have been resettled in Canada by Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) since it negotiated an agreement with the government on March 5, 1979. This historic agreement established the framework for private agencies to sponsor more than 327,000 refugees for resettlement in Canada in the last 40 years.

In the late 1970s, the plight of the “Vietnamese boat people” was highly covered by international media, propelling conversations about refugees and resettlement into public awareness. The end of the Vietnam War in 1975 caused millions of Vietnamese people to flee the country over the next number of years, seeking refuge anywhere they could find it. During the peak of the refugee crisis in 1978, Canadian Mennonites were growing deeply concerned.

The enormous outflow of refugees from Vietnam and Southeast Asia struck a chord that was all too familiar to Mennonite communities, many of whom were themselves descended from refugees fleeing persecution. From its creation in 1920 to the late ’70s, MCC had worked to pay forward that kindness, assisting thousands of European Mennonites seeking resettlement in Canada and the United States after the Second World War and other conflicts and disasters.

The ‘master agreement’

Under new legislation in the 1970s, interested groups of as small as five people could sponsor refugees directly. However, the sponsoring group would also have to accept financial responsibility for the first year of expenses for whomever they sponsored—a daunting obligation that many were unable to risk.

“The request at the MCC annual meeting that year was that I arrange a method or mechanism so that Mennonite congregations could bring in refugees,” said Bill Janzen, then-director of MCC’s Ottawa Office. “The goal was a deal with reasonable clarity as to who would do what, and where the responsibilities of MCC, the churches and government would be clear and manageable.”

Janzen and his MCC colleagues began to meet with officials from the immigration department in an attempt to set in place a master agreement that would allow MCC to bear the burden of responsibility institutionally.

“In Mennonite history and theology, there’s a precedent of the church acting as a distinct social body, to have an impact on injustices,” said Janzen. “Our first instinct isn’t to say, ‘The government should solve this.’ It’s to say, ‘What can we do?’ ”

According to Running on Empty: Canada and the Indochinese Refugees, 1975-1980, by Michael J. Molloy, Peter Duschinsky, Kurt F. Jensen and Robert Shalka, government officials had been told to play hardball and to establish that government supports, like language and job skills training, would be for government refugees only—that MCC would have to create those supports itself, with no assistance.

Shortly after negotiations began, Gordon Barnett, the Department of Immigration’s chief negotiator, realized that an aggressive approach was not going to be the solution.

“As negotiations progressed and the goodwill of MCC became evident, this approach changed, and both sides readily accepted to do what each would do best,” recalled Barnett, as quoted in Running on Empty. “Bill [Janzen] negotiated in such good faith it was embarrassing to play the cards I had been given. . . . Negotiating with MCC demonstrated only their complete commitment to help against our reluctance to give anything up and our meanness. I thought we should adopt a different, more cooperative approach.”

The signing of the “master agreement” on March 5, 1979, marked an extraordinary moment in MCC’s history. While there had been broad agreements in place to support refugee resettlement between MCC and the Canadian government, this deal formed the foundation for how modern faith communities directly support those seeking refuge. Shortly after its signing, dozens of national church bodies and dioceses across Canada signed virtually identical agreements.

Over the following 18 months, half of Canada’s 600 Mennonite and Brethren in Christ churches sponsored some 4,000 refugees for resettlement to Canada.

Resettled, but not yet settled

MCC’s work with refugees doesn’t end when they arrive on Canadian soil. For many newcomers, it means starting an entirely new life in a country where they may not share a language with their neighbours.

Language was not an issue for Jean-Calvin Kitata when he travelled to Burlington, Ont., from his home in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) to attend school. A speaker of 11 languages, including English and French, Kitata only intended to stay in Canada for a year, but a violent coup in his home country meant he couldn’t return, and he applied for refugee status as a student to finish his education in Canada.

Since 2005, he has worked for MCC in Quebec, supporting newcomers, refugees and international students as they navigate their new world. He said his work often involves talking through the deep cultural divides that pervade many areas of the globe.

“I was meeting a newcomer from Burundi for coffee. And the countries in the African Great Lakes Region (Burundi, Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda) have been in conflict for a long time,” he said. “I came back to the table with two cups of coffee, and when I set his down in front of him, he asked if we could switch cups. Even knowing I worked for MCC, he still had fear about being poisoned because of the history between our countries.”

Now, Kitata said, that same man is a close friend and is welcome at his home anytime. It’s that type of transformative peacebuilding that he says drives him to continue his work for MCC.

“When I was a child in Zaire, I went to school with the kids of MCC workers, I ate MCC canned meat, I used MCC comforters,” he said. “Now I’m part of the vision of community and peace of MCC, helping build a family that you can laugh together with or cry with.”

Generational hope

Many refugees coming to Canada are families with young children who may not remember the home they left behind. This, said Kitata, is another aspect to resettlement that is not as simple as some might think.

“Children of immigrants or refugees are often living in two worlds,” said Kitata, whose daughter, the youngest of three, was born in Canada. “They only know life in Canada, but often they’re curious about their parents’ lives before, and have to exist between their parents’ culture and the one around them.”

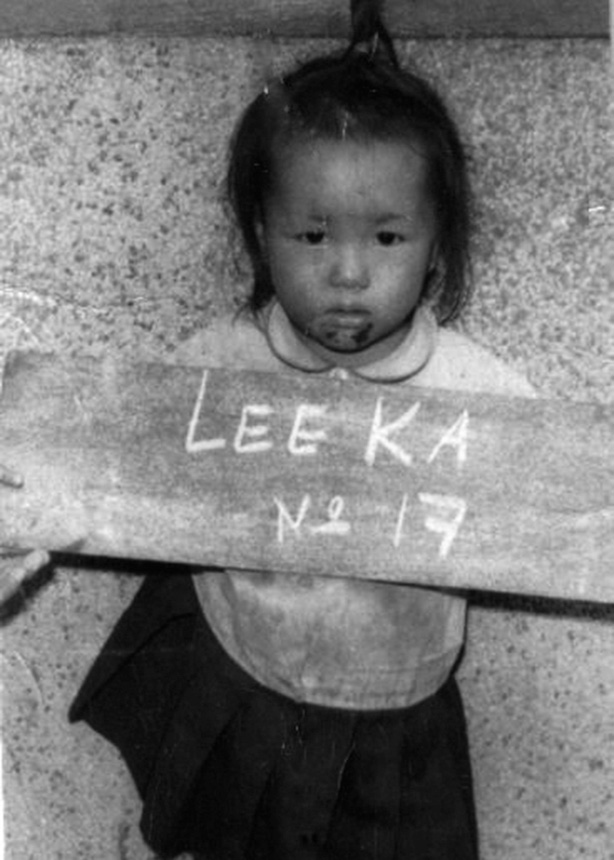

Ka Lee-Paine arrived in Canada 40 years ago and found herself in a very similar situation. Now 42, she was 2 when her parents left the Nong Khai region of Thailand in September 1979 for a new life in Canada. Thanks to the newly signed resettlement agreement, they were sponsored by members of Crosshill (Ont.) Mennonite Church and they settled in nearby New Hamburg.

“There was a lot of ‘that’s not the way we do things’ growing up,” said Lee-Paine. “I wasn’t born here technically, but I’m the only one of my siblings who still speaks the language (Hmong) and really still keeps up some of the culture. I still want to hold on to my culture and belief, but you have to assimilate yourself some, too.”

Balancing two different cultures is not the only challenge she faced as a child of refugees. “When I was 10, I remember having to essentially have my own parent-teacher conferences,” she recalled. “I spoke Hmong and English, so there I was translating everything the teacher was saying to my parents myself.”

She now works as a teacher in Waterloo, Ont., and said she has seen the same situation from the other side of the teacher’s desk.

“I’ve had a lot of students from Syrian families who are in the same situation I was,” she said. “That experience means I can empathize with these kids in a way not a lot of other people can. I’ve had some incredible conversations with young children who I can see are bearing a lot more responsibility than most children are expected to. Children in those situations really need mental health supports and, unfortunately, those can be hard to get for them.”

Lee-Paine said she was immensely thankful for the support her family received when they arrived in Canada, adding that her family is still close with two of the couples who sponsored their journey 40 years ago. They were even invited to Lee-Paine’s wedding in 2009.

“I want people to know that supporting refugees is not something to be afraid of, that they’re only going to add to our society,” she said.

For discussion

1. What experiences have you or your congregation had in resettling refugees in Canada? What was the biggest challenge? What were the rewards of this experience? How long did it take for trust to develop? What would it take for your congregation to do another sponsorship?

2. Did any long-term relationships develop between sponsors and resettled refugees? Do you think close relationships are the norm? What factors can make a sustained relationship challenging?

3. Jason Dueck writes that in the late 1970s the plight of “boat people” from Southeast Asia was widely covered by the international media. Why do you think this tragedy got such widespread coverage? How much are we influenced by what the media chooses to pay attention to?

4. What was so significant about Mennonite Central Committee Canada signing the “master agreement” with the government of Canada in 1979? Why do you think so many churches were willing to participate? Did this change the role of MCC?

—By Barb Draper

Further reading:

'Everything is possible'

MCC representative Victor Neumann, second from left, in Songkhla, Thailand, with Vietnamese Boat People. Mothers of the pictured children were abducted by pirates. In response to the refugee crisis following the end of the Vietnam War, in 1979, MCC was the first agency to sign a private sponsorship agreement with the Government of Canada, leading hundreds of Mennonite and Brethren in Christ churches in Canada to sponsor and resettle thousands of refugees across the country. (All photos courtesy of MCC)

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.