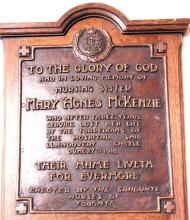

Stephanie Martin had often led practises with the Pax Christi Chorale at Calvin Presbyterian Church in Toronto. But during one practice in 2015 she was drawn to a plaque on the north wall of the sanctuary honouring nurse Mary Agnes ‘Nan’ MacKenzie, “who after three years of service lost her life by the torpedoing of the hospital ship Llandovery Castle, June 27, 1918.”

As the notes to the Llandovery Castle Opera tell it, “Stephanie was both fascinated and unsettled.” She began to have nightmares about the story and so delved deeper.

Returning to Europe after having delivered more than 600 wounded soldiers to Canada from the front lines of the First World War, the Llandovery Castle was clearly marked with large red crosses and was brightly lit up, instead of “running dark” to hide from German submarines. But a German submarine captain, believing the information he had received that the ship was actually ferrying pilots and war materials, sank the ship. On board were 18 Canadian nursing “sisters,” so called even though they were not from a religious order. Their lifeboat’s ropes were entangled, and so by the time it was freed from the sinking ship they were too close and were pulled down by the eddy of the sinking ship. Discovering his error, the U-boat captain gave orders to shoot as many survivors as possible.

Martin knew that the idea of an opera was new ground for her, so she looked for a librettist to write the words to the story in song form. After two years she found Paul Ciufo. With an 11-month deadline to be prepared by the 100th anniversary of the sinking, they drew in the Bicycle Opera Project, and Tom Diamond, an experienced opera director. Ciufo created roles for several of the sisters and for three men, including Helmut Patzig, the German submarine commander.

“I never really imagined that I would be compelled to write music for the bad guy,” says Martin in the notes. But whenever Patzig was stepping to the front of the stage, mechanistic, driving music announced his unmerciful presence to the audience.

Staged on June 26 and 27, 2018, at Calvin Presbyterian Church in Toronto, the production deals with issues of the terror of the conflict with the nurses just behind the front lines, bombardments landing around their field hospitals. There, they must decide who will live and who will die, comforting, patching up, sometimes sending the men back into the line of fire, sometimes holding their hands as they die.

Faith plays an important part, but so does doubt, as characters wonder if they can still believe after seeing Christian nations do so much harm to each other. But they gain—or regain—faith, remembering that they have patched up German soldiers, too.

As the ship sails across the Atlantic and the various characters struggle with fear, faith, their place as women in the world, and even romance, a deck-top worship service serves up a medley of hymns, encompassing Stand by Me, Amazing Grace and an Ave Maria sung in French, that takes centre point of the opera.

When Patzig is deciding whether or not to fire his torpedo, he is surrounded by a chorus of the nurses begging for mercy. And at the end, pointing to the battle of Amiens, where Canadian soldiers were told to take no German soldiers, even if they surrendered, in order to revenge the Llandovery Castle, the women, now dead, gather on stage crying for “no revenge.” In the last chorus, all the voices, including that of Patzig, join in moving toward the light.

In this way, Martin, with Mennonite roots in Ontario’s Waterloo Region, manages to turn a war tragedy into a cry for peace and forgiveness.

Owen McCausland (tenor), left, tells the story of the Dog from Algiers who saves his master’s life on the battlefield to Larissa Koniuk (soprano), Alexandra Beley (mezzo-soprano), and Keith Lam (baritone), in the new Llandovery Castle Opera, whose music was composed by Stephanie Martin. (Photo courtesy of Will Ford, Llandovery Castle Opera)

The plaque commemorating Mary Agnes McKenzie at Calvin Presbyterian Church in Toronto sent Stephanie Martin on her three-year journey to produce the opera Llandovery Castle. Years later, the church installed a stained-glass window above the plaque of Mary and Martha each serving Jesus in their own ways. (Photo by Dave Rogalsky)

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.