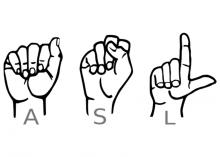

When Canadian students learn an additional language, it’s typically French or Spanish. Not Rachel Braul, though. As a student at Queen Elizabeth High School in Calgary, she learned American Sign Language (ASL).

In addition to its program for students who are deaf and hard of hearing, the school offers ASL courses to the hearing population as an elective, so that they can converse with deaf students.

“Looking back on it, that’s actually a pretty unique experience that not a lot of people have,” says Braul, now 31 and living in Winnipeg. “It spurred on a new interest.”

The experience proved to be formative. A few years ago, while working part-time in a bakery and part-time as a nanny, Braul was considering what she wanted to do next in life. She decided to pursue her interest in ASL and enrol in the ASL-English interpretation program jointly offered by the University of Manitoba (UM) and Red River College. Only about 12 students are typically admitted to the program in any given year. Of the 12 that started in Braul’s cohort, only five graduated.

She graduated from the four-year program this past June with a diploma in ASL-English interpretation from Red River and a bachelor’s degree in linguistics from UM.

“It’s a very challenging program because you’re doing two full-time programs at once, and people often drop out,” she says, adding that while she has graduated and is currently pursuing work as an ASL interpreter, she is by no means an expert.

“You’re honing a skill,” she says of working as an interpreter. “It’s never going to be perfect, it’s never going to be 100 percent. . . . [That’s] what pushed me to keep going. It’s never finished. After four years, I’m still a rookie. I’m a straight-up rookie and I’ll be one for a while.”

According to information released by the Canadian Association of the Deaf in July 2015, there are approximately 357,000 profoundly deaf and deafened Canadians, and possibly 3.21 million hard-of-hearing Canadians.

Interpreters like Braul are available to aid people in a variety of settings, from school lectures and business meetings to religious services and medical appointments. A small but growing number of musicians are also starting to offer ASL interpretation at their concerts.

Braul has a number of things to consider when working with a client, including where best to position herself so that she can both hear the person who is speaking and be seen by the person she is interpreting for.

She also has to check her biases at the door and ensure that she stays composed throughout the booking.

“Advocating for yourself as an interpreter is really important,” she says. “You want to provide the best service possible so that everyone is understood.”

Braul grew up attending Calgary Inter-Mennonite Church in Calgary. She worked as a counsellor at Mennonite Church Alberta’s Camp Valaqua and holds a degree in psychology from Canadian Mennonite University in Winnipeg.

These experiences helped teach her to think critically and consider the experience of others, she says, which helps make her a better interpreter.

“Critical thinking and being able to self-analyze are two huge pieces to being an interpreter, because you’re going into a situation that isn’t yours,” she says. “You’re a third party, and you can affect how people respond to questions. You have to be careful and ask: How am I influencing this situation? You want [the deaf consumer] to have an authentic conversation with whoever they’re talking with.”

“Checking your power, bias, ethics, privilege and power—all of those things I learned through all of my life experiences and through my [CMU] experience,” she adds. “It makes you a trustworthy person as well, if you have all those things in check, and the deaf consumer knows you’re going to do the best job possible.”

Prior to high school, Braul had never met someone who is deaf. That’s not unusual. Typically, hearing people have little or no experience interacting with people who are deaf, so they are intimidated when they do.

“Some hearing people just stare at [them] like a deer in the headlights and then walk away,” Braul says.

Her advice for hearing people who are interacting with a deaf person is straightforward: Consider that person’s feelings and do what you can to accommodate the person who is deaf.

“The everyday barriers a deaf person faces are endless,” she says. “Take the time to recognize that . . . [and] treat everyone the same.”

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.