Many conversations about the Old Testament are determined by questions of modernity. What are the facts? What really happened? The facts are then loaded as ammunition in the culture wars of “liberal” and “conservative.” Other questions bring faith to the shoals of doubt on matters of a potentially violent and misogynistic God.

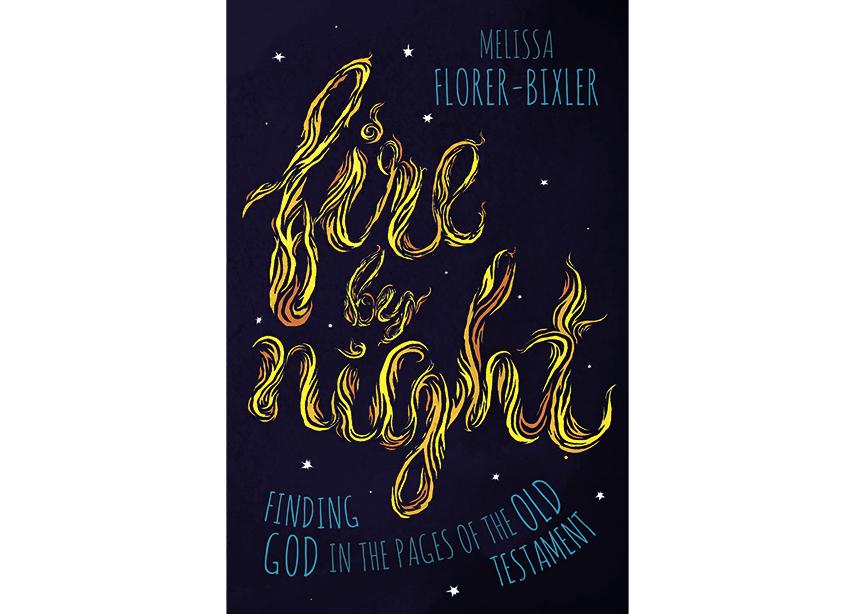

Melissa Florer-Bixler’s Fire by Night makes no attempt to avoid or answer these questions but simply invites us along in a slow reading of the Old Testament within her context of faith.

“Whenever we read the Bible, we participate in a history,” she writes. History remains important, but everything is fair game, including questions of what the text itself might refer to, how the text was formed, how the text formed various communities, and how various communities formed and deployed the meaning of the text. And so, with the Old Testament as an invitation to faith, she invites along, as companions, the voices of monks, Muslims, Jews, children, birds, activists, the incarcerated and those deemed disabled, as well as a host of scholars, authors and regular church folk.

With these voices and stories, Florer-Bixler reflects on a range of passages and offers insightful readings of the practicality of Leviticus, the troubling associations settlers might have with Lot in Genesis 19, the role of remembering violence in the story of Jacob and Esau, and the needed places of both darkness and wonder.

Florer-Bixler has a knack for reading redemptively. What distinguishes her writing from others’ is that she does not appear to approach every text as though there is a “nugget” of redemption always to be found. Rather, there is a trust that the God she is following is indeed a God of redemption, and so it is trust in God rather than an assumption about Scripture that leads her reading.

When reflecting on Lot and his wife in Genesis 19, she gazes long enough at the text and characters to acknowledge her righteous indignation over the evil of Sodom, her dissatisfaction over God’s choice to deliver Lot, and finally her slow acknowledgement of identity with Lot’s wife, who looks back at Sodom, seeing in her a bond to the benefits of structural violence that she too participates in.

We often discard the text once we feel we have found what we are looking for, rather than lingering to allow the relationship to continue its work. Then, with the larger question of God and violence, she is able to accept, citing Walter Brueggemann, that perhaps God is a recovering practitioner of violence.

Accepting this never-ending task of faithful attentiveness allows one the freedom to continue to acknowledge dislike and rejection of texts that have primarily been used for violence in western history. Perhaps nothing has been more devastating than the relationship between western colonialism and the conquest narrative in the Bible.

Rather than trying to redeem these passages—or tear them out of the Bible—Florer-Bixler offers one of the most succinct and yet, to my mind, helpful responses, by simply saying, “There are other passages.” In many ways this is the maddening and inspiring challenge of a faith intimately linked to this book. There is always more. More before the pages were written, more after the final verse, and seemingly always more going on within the book than we can apply a theology to, or a system of ethics can contain. And so, we watch, we follow, we wait, we sing, we listen, we pray, we discuss, we act, we cry, we remain silent, and we watch again.

Fire by Night is a welcome and recommended addition to how we might understand the beautiful and strange entanglement of faith, life and Scripture.

David Driedger is First Mennonite Church of Winnipeg’s associate minister.

More book reviews:

Opioid crisis: A view from the inside

Should we fear the future of technology?

Bible commentary geared for younger readers

'The music ever changing'

Revisiting a third way

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.