There’s nothing comfortable in the artwork of Edgar Heap of Birds. Especially for people whose ancestors came to this continent as settlers.

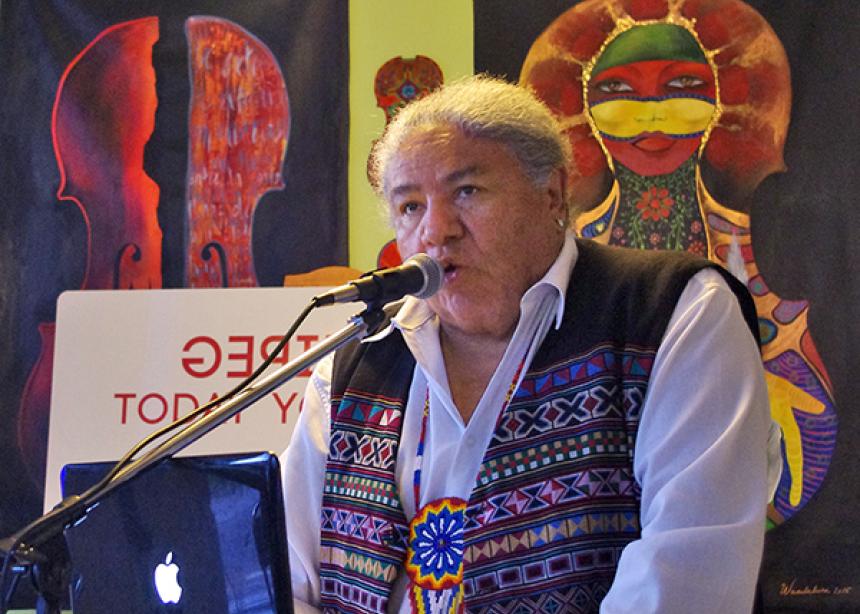

Heap of Birds has described his art as sharp rocks or weapons that puncture First World worldviews. Some felt the prick of that message on Sept. 16, 2015, at Neechi Commons, an upstairs café in Winnipeg’s North End, as they listened to the world-renowned Cheyenne Arapaho artist—who also goes by his indigenous name, Hock E Aye Vi—speak about art, violence, resistance and reconciliation.

Heap of Birds has exhibited his paintings, drawings and text-based conceptual art in galleries all over the world. But it is his public interventions that tend to raise people’s hackles. In 1996, he designed an eight-metre billboard to advertise an exhibit of indigenous art in Cleveland, Ohio. He drew a grinning caricature of the mascot of the Cleveland Indians baseball team next to the words: “Smile for racism.” The private college funding the exhibit was offended by the design and initially refused to allow the billboards to go up. After the controversy made the local news, the school relented.

On another occasion, Heap of Birds installed a series of signs on California trans-it busses that read, “Syphilis/ Smallpox/ Forced Baptisms/ Mission Gifts/ Ending Native Lives.” He had researched the demise of indigenous people in the area and found they were wiped out by diseases brought by missionaries. Those signs were also censored.

“There’s much violence historically in North America,” Heap of Birds told his Winnipeg audience. “My work has been called political or provocative, but it starts out certainly from the reality of the violence.”

Heap of Birds frequently draws attention to the indigenous victims of colonial history. In one of his text-based pieces he juxtaposed the words “Sand Creek” and “Washita River”—locations where U.S. troops massacred indigenous women and children—with “Sandy Hook,” a reference to the 2012 school shooting. “We have more empathy for the kindergarteners than any children who died at Sand Creek or Washita River,” Heap of Birds said. “We should find empathy in all massacres, whether they are white massacres or native massacres.”

The violence of colonialism isn’t just a thing of the past, though. Heap of Birds uses his art to confront the violence of colonialism against indigenous people that he says continues to this day. “Imperial Canada give back stolen lands,” declared a bus shelter sign Heap of Birds created as part of a series labelled “Insurgent messages for Canada.” Another one asked: “Imperial Canada where is your status card?”

“It was certainly a difficult message for some people to hear, particularly for those for whom this was their first foray into any settler-indigenous relations activity,” said Jeff Friesen, associate pastor of Winnipeg’s Charleswood Mennonite, the congregation that organized the event. “Heap of Birds didn’t hold back at all in his message. . . . I think a lot of people came to this event thinking, ‘Oh neat, an indigenous artist,’ and then it was a lot more than that.”

Friesen said people came up to him afterwards with questions: “Everything from wondering why they needed to be feeling guilty about this, to why does the message have to be so strong?”

But being unsettled is a healthy part of the process, Friesen said. “The language of puncture he kept coming back to was fitting. I think he created good and healthy punctures in people’s lives.”

Maya Janzen, who also attends Charleswood Mennonite and helped organize the event, said her church is looking for ways to respond to the recommendations made by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. “I really appreciated Edgar’s art,” she said. “It was inspiring, but also challenging and upsetting, and made me feel uncomfortable at times because I recognize how our city and our country and the things that I participate in are part of the colonial structure.”

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.