Bird-Bent Grass truly is a “memoir, in pieces” as it explores the lives of Kathleen Venema and her mother, with anecdotes from the past, excerpts from old letters and reflections on the present, all mixed together. But the strength of the book is that the pieces fit together to tell the story of a mother-daughter relationship that continues into a painful journey with Alzheimer’s disease. As the stories shift back and forth through the decades, the reader is given an example of how a diseased brain can function in a scattered way.

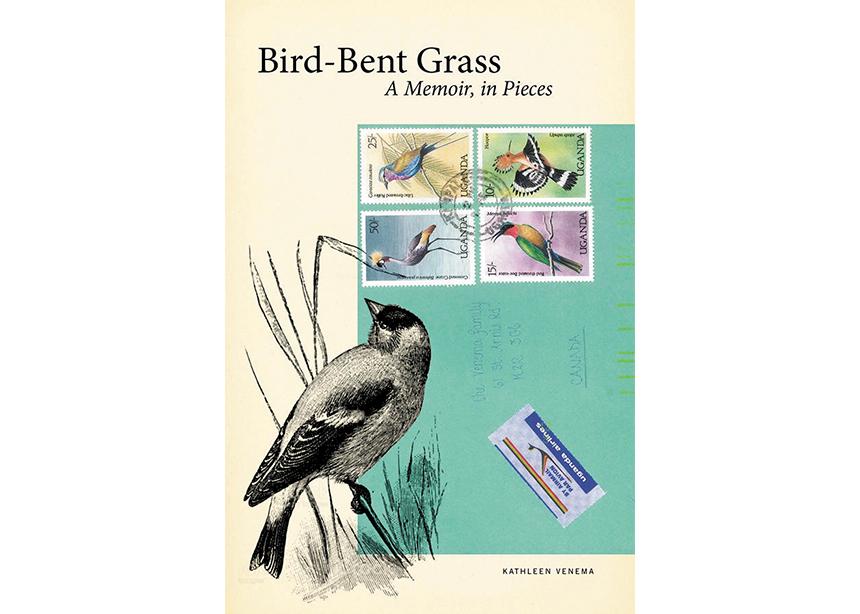

In the 1980s, Venema travelled to Uganda to teach under the auspices of Mennonite Central Committee. This was a challenging time because Uganda was recovering from political unrest and the infrastructure was not dependable. During her time at the school in Ndejje, many letters went back and forth between Canada and Uganda, and these letters are used throughout the book to help tell the story.

The author’s parents were immigrants from the Netherlands after the Second World War. Her mother, who was a child during the Nazi invasion, goes back to many of her childhood memories as her cognitive health declines. Some of these recollections are very painful, but Venema often adds the spark of humour that is so essential in dealing with Alzheimer’s.

Through the letters and Venema’s comments about them years later, we see that her mother is passionate about her faith and is concerned about peace and justice in Canadian society. She is also a deep thinker who enjoys conversations about theology and literature. As Venema contrasts her own life with that of her mother, she is saddened that her mother’s formal education ended so early and she recognizes how blessed she has been with academic opportunity.

Readers who are walking the journey of Alzheimer’s with a loved one should find a sense of rapport with this story. Venema describes the progress of the disease in an honest and straightforward way, tinged with sadness, but always spiced with laughter.

The title comes from a common sight in Uganda, a tiny bird perched on a thin blade of elephant grass, which Venema describes as having “simultaneous serenity and tension.” She thinks of this delicate resilience and tension as symbolizing our existence: Life offers great potential but it is also fleeting and tinged with sorrow.

Although this memoir is “in pieces,” it is very accessible. While the scenes are not in chronological order, Venema describes the situations and emotions of each vignette in a reflective way that brings the characters to life. Many women in the “sandwich generation” should find this book a sympathetic friend.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.