Oliver Friesen’s face lights up when he talks about history. “There’s something about the past,” he says. “It’s alive and so interesting.”

For the past two summers Friesen has been making history come alive for visitors to the Mennonite Heritage Museum in Rosthern. A student of history at the University of Saskatchewan, Friesen has been helping to develop one room of the museum into a Mennonite interpretive centre.

George Epp, who chairs the museum’s board of directors, says visits to other museums convinced the board to move away from “the museum as a repository of artifacts” and towards “the museum as a centre for interpretive storytelling.”

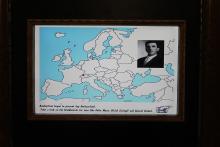

The old red brick building that houses the museum was once home to Rosthern Junior College. As a nod to the building’s academic history, the board chose to use chalkboards as the canvas on which to tell the story of Anabaptist Mennonite origins and eventual settlement in the Rosthern area. Chalkboards lend themselves well to storytelling; as additions and refinements are introduced, “you can take a cloth and change the display in a very short order,” he says.

Friesen agrees, noting that as he works on the chalkboards he thinks of other things that could be changed or improved. “You could spend so much time just on the chalkboards,” he says.

But Epp and Friesen have been careful not to overwhelm visitors with printed text. Snippets of information are offered with illustrations, and beneath the panels museum artifacts add another visual dimension to the story. For those who wish to read more, the story continues on printed handouts that visitors can take with them.

In addition to the chalkboards, the room boasts an interactive digital installation. Created by Wes Ens, the installation features an animated tour guide that leads visitors through Anabaptist Mennonite history from the days of Felix Manz and Georg Blaurock to 21st-century Rosthern.

Epp says the interpretive centre is designed to appeal to a broad range of visitors. School groups may engage in a museum scavenger hunt, while adults might choose to do research using the museum’s growing library of community and family history books.

Friesen estimates that about 50 percent of visitors are Mennonite. “They want to know whether we have information regarding their families,” he says. “They want to connect with their history.”

Others who step through the door have no idea who Mennonites are. Friesen says they will ask questions such as, “So what is a Mennonite?” and, “Are Mennonites Russian?” When he tells them about the early Anabaptists and what Mennonites believe, he says the conversation then “shifts toward religion and how people should treat each other.”

Friesen says he has always had a passion for history but was never interested in the Mennonite kind until recently. Working at the museum has helped him discover his immediate family history, as well as the faith story of his Anabaptist forbears.

He indicates a family photograph on display in the room. “I look at a picture like that and I imagine what was happening in the family moments before the picture was taken,” he says. “There is so much more [to history] than what we see.”

He hopes that Mennonite visitors to the museum will come away knowing that their heritage is valuable. “The Mennonite story is fascinating and adventurous,” he says. “People died for their faith. People left their homeland. It’s important to know your heritage, but it’s also exciting.”

For those who aren’t Mennonite, he hopes a tour through the museum’s interpretive centre will spark an interest in learning about their own heritage. “It’s important to know your own identity and history,” he says.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.