When Dan Driediger closes his eyes, he sees rivers, rises and roads. His unique photographic memory comes in handy. Driediger is a cartographer: He creates, prints and sells maps to people and organizations across Canada.

Driediger, a life-long outdoor adventurer and enthusiast, began his foray into map-making in 2011. While in university, he did some casual work for a map company, squeezing work in when he “didn’t want to do homework.” His work in the field increased during pandemic lockdowns, and in 2021, he bought the company when the owner retired.

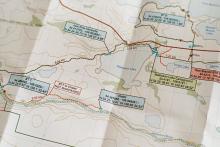

The process of creating a map is long and complicated. When Driediger receives a request for a new map, he first extracts the data for that particular area from a Government of Canada website and then imports it into the map making program on his computer. The raw data, while complete, would not make sense to an average person. He then spends hours making sense of the information by dealing with layers, such as roads, lakes and contour lines. Then each layer is manipulated further to determine the order of layers and the thickness of the lines in each layer.

“The easiest thing I can compare it to is composing a song,” says Driediger. “Each layer is like adding each instrument. Different instruments need to come in at different times and in different ways to make the final composition perfect.”

Some of his maps have taken more than 100 hours to complete. Last year, his company sold over 5,000 maps, and he expects to sell even more this year. In the winter months, when sales are slower, he devotes his time to creating new maps. The problem, he says, is that there are always more maps to make than he has time to create.

Dan runs his business out of his home in Missinipe, Saskatchewan, 455 kilometres north of Saskatoon. Even though his remote location means a two-hour round trip to the nearest post office twice a week to mail out his maps, he wouldn’t have it any other way. “I love it here, absolutely love it. I get to live where I want to live, and do my passion. Buying the company meant I got to take it by the reins and run with it.”

Even in an age when most people use Google for navigation, Driediger sees value in physical, printed maps. “The difference between a paper map and looking at a digital map on your phone is that on your phone, when you look at something, you can’t zoom in and see a wide area at the same time; you can’t see close up while looking at the other side. . . . And what happens when you have no battery or your phone goes swimming? Why not have a waterproof map that you can leave outside all summer?” he said.

The most life-giving part of his business, he says, is the chance to travel to new regions of Canada without ever leaving his office. Often, Driediger will create new hiking and canoeing maps based on the notes and journals of fellow outdoor enthusiasts. Contacts will give him their trip journals with details such as what’s around the river bend, portage locations, and portage length. “It’s so much fun to go on people’s trips with them and relive the journey with them. I get to go with them on their trip through their notes,” he said. “I can take a good set of notes and turn that into a map. I have somewhat of a photographic memory for locations and topography, which is perfect because you gotta know it through and through to make a good map.”

Do you have a story idea about Mennonites in Saskatchewan? Send it to Emily Summach at sk@canadianmennonite.org.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.