While people across Canada and around the world self-isolate from COVID-19, work continues on the Coastal GasLink (CGL) pipeline in northern British Columbia, without the full consent of the Wet’suwet’en people. The 670-kilometre long pipeline plans to snake through Wet’suwet’en territory and export liquefied natural gas around the world.

Steve Heinrichs, director of Indigenous-Settler Relations with Mennonite Church Canada, volunteered on Wet’suwet’en territory with Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT) from March 3 to 17. He was not serving on behalf of the nationwide church, but, instead, used vacation time away from his job to independently volunteer.

Instead of assuming the typical CPT role of conflict intervention and de-escalation, Heinrichs and his fellow CPT volunteer, Emily Green, were invited by land defenders to observe and document the actions of CGL and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), to create a legal record of everything taking place.

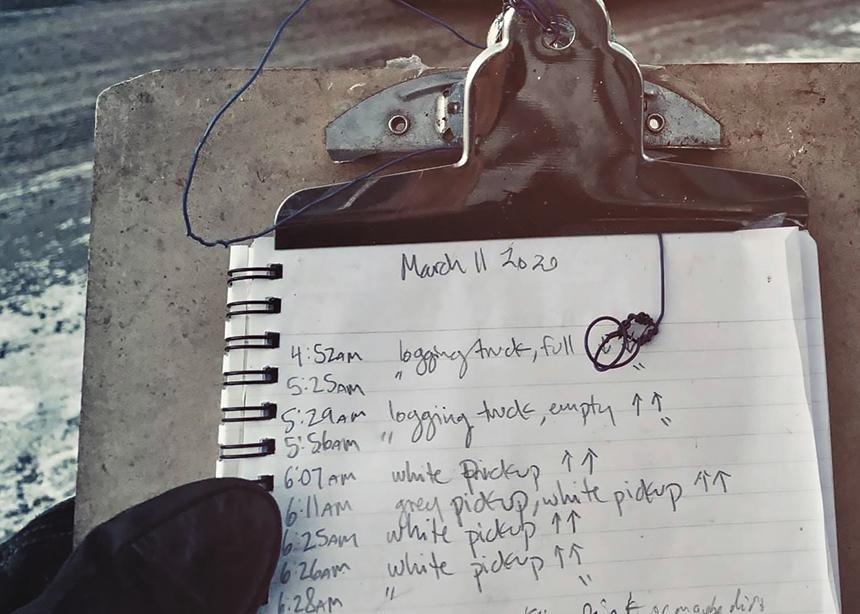

They joined the 27km Camp, where they did a 24-hour-a-day watch of the Morris Forest Service Road, monitoring RCMP and CGL presence and noting license plates, vehicle descriptions and their actions. Heinrichs also helped with cooking meals, washing dishes, chopping firewood and building a boardwalk.

Numerous times while Heinrichs was on road watch, those in the vehicles passing through took pictures of him and the other observers, honking at them, making offensive gestures and swerving in front of them. “Taking shifts between two and four in the morning was cold, but stars were beautiful,” he says. “But strange to see RCMP still going back and forth on occasion during those hours.”

Extractive projects are still considered essential services right now, even though the work environment contradicts the government’s physical distancing demands and endangers Indigenous communities that are already more vulnerable due to inadequate access to services like health care, clean water and housing.

Heinrichs arrived on Wet’suwet’en territory at a unique time, right as talks between the federal and provincial governments and hereditary chiefs were taking place in Smithers, B.C. While there were no RCMP officers in full military gear or helicopters, the everyday violence persisted, he says. “At the same time that the Crown is sitting down with hereditary leaders discussing Aboriginal title and rights . . . [CGL] is doing a ton of work in the territory,” chaperoned by the Crown’s police, he says.

As many point out, there is a diversity of opinions about the pipeline among the Wet’suwet’en people. “And yet the deeper question is around jurisdiction,” says Heinrichs. For decades, the government has put off settling the land rights question and used it in its favour to extract as it wishes, saying projects can go forward while the question remains unresolved. Heinrichs says there should be a moratorium on all work until that is figured out. “I recognize that a lot of people in society don’t see that as violent activity, but it is violent because it’s a violation of Indigenous law in the ground.”

Heinrichs is passionate about this because he is a Mennonite. “Here we are in Holy Week,” he says. “It’s the story of God become poor to walk with suffering peoples and went to the ultimate lengths to stand in solidarity with vulnerable and hurting peoples who did not have the power to have their voice and their concerns and their well-being honoured. And I think that’s the call of the church.”

But it isn’t just the gospel that powers his convictions. It’s the history of his Mennonite community, too. “Our memory within the Mennonite church, I think, sometimes can be very short,” he says. “We think this kind of work is radical or it’s just what CPT does, but we forget that we actually do have a tradition of, at the very least, recognizing in public word that we should be in solidarity with Indigenous peoples.”

At the 1970 Conference of Mennonites in Canada gathering in Winkler, Man., the delegate body prayed a corporate litany of confession to Indigenous peoples.

In 1977, Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) published a statement expressing solidarity with northern Indigenous communities on matters of industrial development. The Conference of Mennonites in Canada affirmed a resolution supporting this statement.

MCC supported a new covenant recognizing Indigenous self-determination and land reparation in 1987, which was reaffirmed in 2007 by both MCC and the nationwide church.

At the nationwide gathering in Saskatchewan in 2016, the church repudiated the Doctrine of Discovery.

Heinrichs is currently working on a book with Esther Epp-Tiessen, the former public engagement coordinator at the MCC Ottawa Office. The book compiles the Mennonite community’s many statements on Indigenous solidarity over the years. MCC and MC Canada are co-producing the publication, which they are hoping to release this fall. Working on the book has been encouraging for Heinrichs, who hopes that learning this history will empower more people to take action.

Learn more about the Wet’suwet’en land rights conflict from resources compiled by Heinrichs, available at bit.ly/3eq5nEf.

Do you have a story idea about Mennonites in Manitoba? Send it to Nicolien Klassen-Wiebe at mb@canadianmennonite.org.

Related stories:

The perfect complexity of Coastal GasLink protests

In response to blockades: prayerful pause

Who do you support when a community is divided?

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.