It doesn’t seem right that more people aren’t familiar with singer-songwriter Paul Bergman.

Over the past 12 years, Bergman has quietly released five albums. Steeped in the tradition of songwriting legends like Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen and Tom Waits, the 32-year-old’s music is carefully crafted and displays a unique voice reflecting on rural life, death and the ways people connect—or fail to connect—with their surroundings.

“He’s entirely too well-kept a secret,” says Darryl Neustaedter Barg, who recorded Bergman’s first four albums: 2003’s Po’ Lazarus, 2005’s As For Me and My House, 2006’s Rootbound and 2008’s Crow Scarecrow. “[His songs] sound so simple, but once you start paying attention to the lyrics, you realize there are some very thoughtful things going on… I’ve never met anybody who works as hard as he does on his songs.”

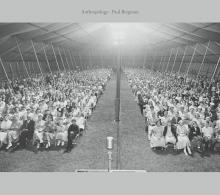

Bergman released his fifth album, Anthropology, this past November. It’s his most varied collection of songs to date. Just like his previous releases—and, as the title suggests—it’s a study of humankind.

Released in the span of five years, each of Bergman’s first four albums were recorded live off the floor in a matter of days. Bergman wanted to give Anthropology more time.

“I [told myself]… I’m not going to release this thing until I’ve got a batch of songs that I feel have moved me before I can even think about hoping that they might move the listener,” Bergman says by phone from his home in Altona, Man., 100 km. south of Winnipeg.

Recording spanned four years and a number of locations. Two of Winnipeg’s top recording engineers, John Paul Peters and Michael P. Falk, were involved, as well as a handful of the city’s most in-demand musicians, including jazz drummer Curtis Nowosad and pedal steel master Bill Western.

The album opens with “Down a Dirt Road,” a track inspired by an old gospel song. Bergman initially envisioned a full band playing on the song, but ended up going with a sparse arrangement that features just his voice and acoustic guitar.

Barely one minute long, the song was recorded in a friend’s barn one August evening as a thunderstorm rolled in. He recorded the song 33 times. Take 27 made it onto the album.

“It sort of sounded like an old field recording,” Bergman says. “You could hear the crickets and the creaking chair, and it was all just very present and it seemed to fit the sort of unknownness of the song, better than some of those more fully-rendered versions were able to do.”

On the other end of the spectrum, in terms of both production and sound, is the album’s fifth track, “Albert Johnson,” an atmospheric, seven-minute song with haunting guitar lines comparable to early ‘90s U2.

With sorrowful violin and pedal steel lines playing in the background, Bergman sings about Albert Johnson, a 1930s fugitive in northern Canada. Johnson’s refusal to answer questions about traplines he was suspected of tampering with sparked an RCMP manhunt and an eventual firefight that resulted in his death.

Bergman was inspired to write the song after reading The Mad Trapper, Rudy Wiebe’s 2003 novel about the incident.

“It’s a remarkably sad story and remarkably odd. It’s tough to say why it grabbed me, but it just seemed to want documenting and telling at some level,” Bergman says.

“One of the inescapable themes of this record at least, and maybe my writing more generally, it’s always about connection and one’s inability to connect in any relationship—one’s relationship with one’s self or one’s town, or one’s family or whatever it may be, and just how difficult and how fraught all of those relationships are.”

Although less overtly on Anthropology than on previous albums, faith and Mennonite culture are recurring themes in Bergman’s work. He grew up at Altona Bergthaler Mennonite Church but no longer attends.

Still, his Winnipeg album release concert—held in a chapel at the University of Manitoba—felt almost worshipful, and ended with Bergman inviting the audience to join him in singing, “This Little Light of Mine.”

“It’s such a good philosophy and it’s such a good note to end off on,” Bergman says of the song. “At the end of the day, what bloody else is there to do? We all have our little offering and you just better offer it.”

Time will tell whether or not Bergman’s little offering remains a well-kept secret or reaches a wider audience with Anthropology.

“I hope to create moving and applicable music that might accompany people through their lives,” he says. “As for how many people that is, that’s a different discussion almost. If that is 50 people or if that is 50 million, there’s merit in all of that to me.”

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.