The Christ Child has arrived. We’ve waited through four weeks of Advent to light that fifth candle, the Christ candle, symbolizing the presence of Christ in our midst. And we feel ready to welcome this baby with open arms. Don’t we?

It’s easy to forget, I think, that the Christ Child received rather contradictory messages at his birth. Some, including his parents, the shepherds and wise men, the angels, even the friendly beasts—perhaps representing creation—offered him clear welcome. But others, like the innkeeper, turned his family and him away, or, like King Herold and Emperor Augustus, acted with overt hostility toward them. And this pronounced lack of welcome is not to be taken lightly in that cultural context, with its emphasis on hospitality, on welcoming not only the friend but also the stranger.

Mary of Nazareth is the first to provide this kind of welcome, with her “yes” to the angel Gabriel. In a way, hers was the ultimate instance of welcoming the stranger, since she was welcoming and making space for the very otherness of God. So what fostered in Mary this kind of radical openness? Her revolutionary hymn, the Magnificat, attests that Mary was steeped in her own Jewish tradition and Scriptures, and she most certainly would have been familiar with the key biblical notion of welcoming the stranger.

Appearing four times in the first five books of the Bible, from Genesis to Deuteronomy, the command to love or welcome the stranger—also termed “resident alien” or “foreigner”—was central in Israelite understanding, and was linked with the care for widows and orphans, or “the least” of that society and context. In Deuteronomy 24, the Israelites are commanded “not [to] deprive a resident alien or an orphan of justice; you shall not take a widow’s garment in pledge. Remember that you were a slave in Egypt. . . .” They are also to leave food—grain and olives and grapes—for “aliens,” orphans and widows to glean, a system of sharing at work in the Book of Ruth.

In these passages, God calls on Israel to extend a particular welcome to the outsider, the one not at home, the one who is vulnerable and thus in need of hospitality. Isn’t it likely that Mary drew on this tradition when faced with the ultimate stranger, the one who was radically other and yet became completely vulnerable, the God Child, Jesus? In God’s act of becoming a human child within her, Mary read God’s love for the most vulnerable: for herself as a young peasant woman, pregnant and unmarried; for her nation, straining under Roman occupation; for all the humble, meek and hungry over the proud and the rich. And she responded with reciprocal love and welcome and hope. Without any guarantees, she agreed to make God’s plan possible by mothering Jesus.

And from the start, it wasn’t easy. This makes Mary’s profound hospitality all the more remarkable, as she offered what she herself, and her son after her, were continually denied. Think of her story in Luke 2 and Matthew 2. Near the end of her pregnancy, she was forced to travel to Bethlehem to be taxed, an excruciatingly uncomfortable journey that may have caused her to go into early labour. And there, in Bethlehem, there was no room for her and Joseph, and she had to labour and give birth in a stable.

In Rediscovering Mary: Insights from the Gospels, theologian Tina Beattie speaks of Jesus’ birth as Mary’s “own physical passion,” stating, “Rejected by society and lying in a barn among animals, she suffered for the salvation of the world.” Afterwards, Mary and Joseph fled to Egypt as refugees, unable to find any safety or home in their own land.

And, of course, in the ultimate rejection of Jesus—his death on the cross, when evil and sin tried to render Christ utterly unwelcome—Mary was subjected to one of the worst forms of grief: the violent death of her son. Despite, and in the face of, all of this rejection and unwelcome that was to come, the Incarnation began with Mary saying “yes” to God’s request for hospitality.

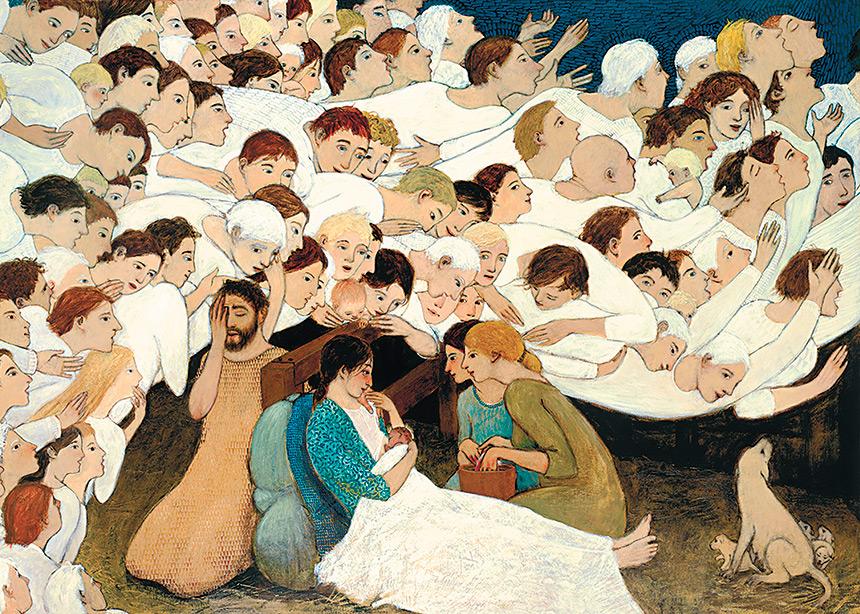

Of course, there were others who welcomed the Christ Child as well. In his oil painting simply entitled “Nativity,” pictured above, artist Brian Kershisnik speaks of the angels as a “cloud of witnesses” or a “river of angels,” which crowd closely around the holy family, and then turn their faces heavenward to praise God for what they have seen. Notice the tired-looking Mary, the agony—or is it relief—of Joseph, the two midwives looking on, even a dog and her puppies in the corner, perhaps representing the “friendly beasts.”

In “Nativity: An essay,” Kershisnik speaks about the scene:

“Jesus came very much like you and I came. His birth was like your birth and mine. He came into our dirt and sweat and blood and milk. . . . His birth was, in that sense, unremarkable. It hurt his mother and him.

“It was very likely troubling to Joseph as well (his vexation probably complicated by their displacement from home) and likely not so troubling to the midwives, smiling through the bloody ordeal, as midwives do. I know that no midwives are mentioned in the Scriptures, but bear in mind that almost none of the details of his birth are mentioned in these holy texts. Even the stable is inferred by the brief mention of an improvised cradle—his being ‘laid in a manger.’ The chance of a young woman having her first child away from her usual residence, and not being attended to by women [even strangers], seems to me very unlikely. Women would come. They would hear; they would help. I feel sure of it.

“Perhaps the sheer number of them is a clear indication that I became engaged with the angels [who almost fill the five-metre-long painting]. The births of my own children felt so very ‘attended to’ by otherworldly beings. . . . The number of angels in my work kept multiplying. I have counted them several times, but I come up with different numbers. I rather like not knowing exactly. . . . [And that] only the dog can see the glorious river of angels.”

For me, it’s striking to notice that there is actually no stable depicted in Kershisnik’s art. Instead, it is the angels who shelter and surround the newborn baby and his perplexed parents. And the angels’ curiosity and wonder are almost child-like, kind of like our restless little angels and wise men who crowded in close to baby Dominic at the nativity play last Sunday evening!

What, then, is our calling, as followers of Mary’s son? Perhaps drawing on something his mother taught him, Jesus reaffirms and reinterprets the idea of welcoming the stranger in Matthew 25, in the parable of the sheep and the goats. Among other acts of mercy, he lists, “I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” And when they wonder when it was that they offered him hospitality, he says, “Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.” In Jesus’ interpretation, the “least” are to be viewed as the face of Christ himself, as God-with-us.

These days, it can sometimes seem that there is increasing fear around welcoming strangers or refugees, which speaks of a broader distrust of diversity and difference. In times like these, this idea of making space for a stranger seems vastly removed from our reality, a naïve hope. Yet there are instances of this kind of welcome all around us, from Nutana Park’s own decades-long involvement in literally welcoming the stranger by sponsoring refugees or newcomers to Canada, to other forms of intentional welcome for other people who have been made “strangers” or vulnerable, people who are presumed not to belong or not to matter.

As we welcome the Christ Child today, let’s remember that we are called to be those witnesses, called to form a river of angels that shelters the homeless, the displaced, the refugees, the strangers, all of whom are the face of Christ. So in a world that so often turns vulnerable people away, let’s continue to be people of welcome, knowing that through our hospitality, God is able to make strangers into kin.

Susanne Guenther Loewen is co-pastor of Nutana Park Mennonite Church, Saskatoon.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.