Immediately after finishing with undergraduate school in 2008, I went down to Mexico to help translate for a mission trip that my mom and younger brother were taking with my church’s youth group.

One day, the Mexican pastor we were working with—a smiling, mustachioed man who led a tiny Pentecostal church called Jehovah’s Hand—informed me that I was going to preach a sermon at the Wednesday evening service. This took me aback. I had never preached a sermon before. I had certainly never preached a sermon in Spanish before. And prior to that week, I had had little to no experience with the charismatic brand of Christianity practised by these Mexican brothers and sisters.

What could I—a white, wealthy, evangelical Anglophone—say that would be meaningful or relevant to a congregation of poor Mexican Pentecostals? That week, I had already felt lost and a bit overwhelmed by worship that involved more than an hour of deafening praise choruses that seemed to repeat endlessly, during which congregants would burst into ecstatic, incomprehensible utterances as the Spirit moved them, or fall to the floor, “slain in the Spirit,” when someone laid hands upon them to pray for them. I could not understand these expressions of faith, so how was I supposed to speak to them, particularly when I had less than a day to prepare a message in a language that I had learned almost exclusively through school courses?

What immediately came to mind was I Corinthians 12, in which Paul talks about the church as a body: “[f]or as the body is one, and hath many members, and all the members of that body, being many, are [nonetheless but] one body, so also is Christ.”

I had always understood this passage as referring to individuals within a congregational body. However, in light of what I had seen at Jehovah’s Hand, I began to wonder, might this same principle not also apply on a larger scale, to the global body of Christ? “For to one is given by the Spirit the word of wisdom; to another, a word of knowledge, by the same Spirit; to another, faith by the same Spirit; to another, gifts of healing by the same Spirit.”

I could identify with this initial list of spiritual gifts. In my own church upbringing, “knowledge” and “wisdom,” generally understood in terms of sound biblical exegesis, were the central foci of church life and worship, and “healing” of emotions, relationships and bodies was an expected outcome of the Spirit’s presence, although these were typically effected through the mediation of medical professionals rather than the direct intervention of the Holy Spirit.

But what of the other gifts? “To another [is given] the working of miracles; to another, prophecy; to another, discerning of spirits; to another, diverse kinds of tongues; to another, interpretation of tongues.” Quite frankly, my North American church experience had offered me little preparation for my encounter with such “gifts.”

But what did the Apostle Paul himself have to say about this? “But all these work that one and the selfsame Spirit, dividing to every man as He will”—and, I would think, to each woman, church and culture as well, whether we be rich or poor; white, black or brown; conservative or liberal. We “have been all made to drink into one Spirit.”

This revolutionary claim means that it is not enough to say, in a postmodern fashion, that I do my thing, you do yours, and as long as we don’t talk about it, we’ll get along fine. Rather, Paul calls the church to recognize that we must not only be tolerant of these diverse manifestations of the Spirit within the church, but we must recognize that we, ourselves, are incomplete without them.

Scottish historian Andrew Walls has called this coming together of diverse members an “Ephesian moment.” The first-generation church at Antioch experienced a paradigm shift in its understanding of what it means to be the people of God through the realization of the reconciliation that Christ brings about: “He himself is our peace, who has made both one, and has broken down the middle wall of partition between us” (Ephesians 2). As a direct result of this supernatural act of reconciliation in Christ, Walls notes that Jews and Gentiles, for the first time in history, could enjoy table fellowship without giving up their cultural identity, since the old markers of Jew and gentile had been subsumed and transformed by the person of Christ.

However, I believe that the nearly 1,500 years in which Christianity has been predominantly the preserve of European culture and intellectual heritage may have in some way obscured the practical significance of these words for us today.

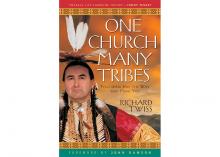

First Nations theologian Richard Twiss argues in his book One Church, Many Tribes that “[i]t may be difficult to hear or accept, but I believe that because of clashing cultural worldviews, the Anglo expression of Christ and his kingdom has said to the Native expression of Christ and his kingdom, ‘I have no need of you. I don’t need your customs, your arts, your society, your language, concepts or perspectives.’ If you look at a thing and cannot identify value in it, you will have no perceived sense of need for it. And if you have no need for it, then you get along without it. Then, to add injury to insult, the Euro-Americans have said to the Natives, ‘But you need us. You need our theology, our leadership, our traditions, our economic resources, education, sciences, Sunday schools—ultimately, our civilization.’ Anglo Christians need to understand that these are some of the painful issues their Native brethren struggle with. Without understanding, there is no basis for compassionate change or the possibility of partnership.”

I believe that what Twiss observes with respect to First Nations Christians is true of the church worldwide. Wherever there are non-European churches, there is a tendency for the older and more established churches of Europe and North America to view them as, in Twiss’s words, “a needy but largely forgotten mission field, a group in need of receiving ministry.”

Anglophone Christians who self-identify as “conservative” or “evangelical” both:

- Often smell heresy when theologians of the Global South claim that issues of economic justice are, indeed, “spiritual” issues;

- Are often outraged by the strong stance that Southern Christians (particularly Africans) have taken against homosexuality; and

- Are generally taken aback, as I was, by the Pentecostal and oftentimes “prosperity gospel” flavour of Southern Christian faith.

All of these reactions reflect a tacit assumption that it is our church that is the full measure of the gospel, and to the extent that they fail to look like us, non-Western Christians are in some way deficient.

Twiss holds that “the non-Native evangelical community has yet to say to the Native American Christian community, ‘We need you.’ Why not? Because differing cultural worldviews determine how value is assigned, measured or determined, whether for a person, group or thing.” As a corrective against this spiritual pride and disdain, he says that he “would love to see some of our Anglo church leaders, when asked to help a Native church, say, ‘Yes, but on one condition: only if you will in turn send your pastors and leaders to come and equip us with the grace and gifting God has given you as Native people.’ When that day comes, it will verify that we are seen by our Anglo brethren as equal collaborators in the mission of the church.”

I don’t know if any of my Mexican brothers and sisters got anything out of my stumbling meditations on I Corinthians 12 that night many years ago, but I know that God used that night to speak to me.

While I don’t want to give the impression that the West has no gifts to offer the global church, too often we assume that it is our wealth and our wisdom that will be the world’s salvation. The West, in fact, has many gifts to bring to the global church, but for those gifts to be received, we must hear and heed the words of the One who bids us “buy of me gold tried in the fire, that you may be rich, and white raiment, that you may be clothed, and that the shame of your nakedness do not appear; and anoint your eyes with eye salve, that you may see” (Revelation 3:18).

Only by coming to our brothers and sisters in a posture of humility, acknowledging our need, and being willing to learn and receive, will we be able to offer our gifts and take our place among the global church across space and time, bringing together “the glory and the honour” of all nations into the heavenly Jerusalem.

Adapted from a sermon preached at Point Grey Inter-Mennonite Church, Vancouver, on Aug. 18, 2013. Michael Thomas focussed on world Christianity for his master’s thesis at Regent College in Vancouver, B.C., travelling to Ghana’s Akrofi-Christaller Institute to conduct research on African approaches to theological education. He teaches at Cedar Tree Classical Christian School in Vancouver, Wash., where he lives with his wife Jenn, and Elsie, their six-month-old daughter.

For discussion

1. Do you enjoy trying new experiences in worship? Have you ever been in a worship service where there were ecstatic utterances or people “slain in the Spirit”? What was your response to this kind of worship? What are some Christian worship customs used by others such as Global South or First Nations congregations that might feel strange to you?

2. Michael Thomas suggests that people from older, more established Christian churches tend to view non-European churches as needing guidance to know how to worship properly. Do you agree? Has this view been changing over the last number of decades?

3. Are you aware of Mennonite churches in Canada where people have gifts of miraculous powers, speaking in tongues or interpreting tongues? What benefits could these or other spiritual practices bring to our churches? Are there ways in which our worship is deficient?

4. How could our churches take steps to be in a “posture of humility, acknowledging our need and being willing to learn and receive” from other cultures? When the churches of Mennonite World Conference get together, are some worship practices considered more acceptable than others?

—By Barb Draper

“While I don’t want to give the impression that the West has no gifts to offer the global church, too often we assume that it is our wealth and our wisdom that will be the world’s greatest salvation.” (Art: ‘Christ and the Rich Young Ruler’ by Heinrich Hofmann)

“What could I—a white, wealthy evangelical Anglophone—say that would be meaningful or relevant to a congregation of poor Mexican Pentecostals?” (Photo courtesy of Michael Thomas)

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.