God’s creation is now facing unprecedented destruction brought on by human activity. Attentive hunters know this just as well as vegan environmentalists.

Caring for the ecosystems that God created doesn’t need to be a divisive or partisan issue. Yet it has come to feel that way. Conversations related to energy have become especially contentious. This is challenging since the generation, distribution and use of energy represents the most significant long-term threat to creation’s well-being, including landscapes that many of us love.

The long-term effects of climate change are disastrous, especially for places and people on the margins of geo-political and economic power. The trajectory is so clear that governments and businesses around the world are looking for ways to mitigate the impact of a changing climate.

Given how much is at stake, it’s hard to understand why we haven’t been more responsible and effective in our approach to energy and its impact on God’s creation. It’s particularly surprising that communities of faith haven’t been more engaged.

At a recent public lecture in Kitchener, Ont., the province’s environmental commissioner lamented that during her three years in office she was unaware of a single delegation of faith leaders approaching the provincial government with concerns about climate change. What has caused this perplexing silence?

It may be that faith communities think the issue is too big or too polarizing. We might think that serious climate action is at odds with traditional livelihoods like farming or logging. Or we might think that our communities can’t do much to effect change.

Whatever the reasons for our silence, the Bible makes our obligation clear. God calls creation “good” repeatedly. And that’s even true before humans were brought into being (Genesis 1:10,12,18,25). Genesis tells us that the humans were created in the image of the One who delights in creation (1:26); it also tells us that humans have been tasked with serving and protecting God’s good world (2:15).

Throughout the Torah God teaches people to honour the land that they steward. For instance, in Deuteronomy 20:19 God instructs the Israelites not to cut down the fruit trees in battle: “Are the trees people, that you should destroy them?” It’s an odd line for pacifists to read, but it shows that people aren’t the only living things that matter.

The Psalms contain many examples of God taking delight in creation (19,24,104).

The prophets also fold creation care into their calls for justice. In the first verses of Hosea 4 human irresponsibility is linked to the devastation of ecosystems.

And let’s not forget Jesus’ words in Luke 12:6, that speak to God’s care for small creatures like birds. This baseline of careful stewardship is recognized by Christians of every stripe.

There is an even sharper edge to the biblical perspective, however. It is the conviction that non-human creation has its own relationship with God. Stewardship and responsibility are important, but these concepts are too tame to capture a biblical theology of creation. Psalm 148 tells us that creation praises God, while Romans 8:18-25 tells us that creation groans to God, waiting for liberation.

Is it too radical to say that humans aren’t the only created things that pray? The earth, the biosphere, the innumerable plants and animals all have their own standing before God. None of it is ours. Looking through this biblical lens at our modern lives and the energy they require, it becomes clear that something has to change.

A call for creative, collective and transformative action

While personal initiatives are good places to begin, we need transformative and consequential change. Transformative action is the kind that fundamentally challenges the way we think about energy and how we generate it. Christian communities are well placed to facilitate this transformation. They can take creative, collective action that has a substantial, direct impact, and sets an example for our communities at large.

This kind of thing is not new for Christians. The New Testament shows how early churches found powerful ways to counteract harmful norms. They found ways to share across wide economic disparities. They were able to see a common humanity and common status before God despite significant ethnic differences.

Christian communities have been complicit in more than their share of harmful things. Nevertheless, communities of people following Jesus have also provided access to healthcare and education, dignity and freedom for many who lacked them. Communities attentive to God’s Spirit have turned things on their head before.

Christian communities can make a difference in the current climate crises. Here are some places to start:

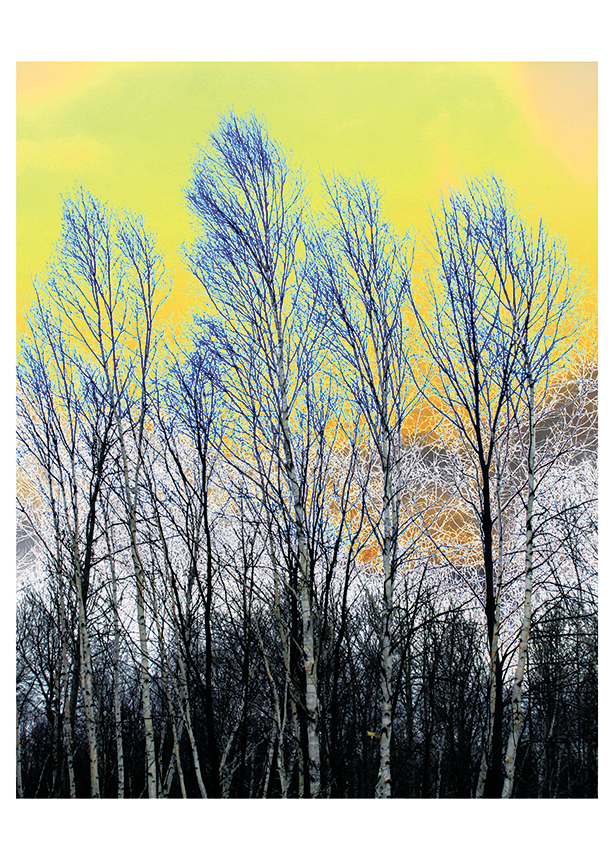

1. Connect to places that inspire our care for creation

We can nurture love for our bioregion (a land and water territory whose limits are defined by the geographical limits of human communities and ecological systems). We can encourage each other to get outside. We can find one nature-related thing to dig into, maybe learning the names of all the birds in our area, or learning to identify native trees or wildflowers. We can learn how First Nations have, and still do, care for these places. Congregational leaders can employ natural images in worship. They can hold church outside, maybe using resources from the forest church movement.

2. Learn from real-life examples

Communities around the world are creating inspiring versions of life that rely on small-scale, decentralized, local energy sources.

A fascinating example is the Solar Mamas social entrepreneurship business model that began in India. It has brought sustainable solar energy to over a thousand communities across the Global South.

Exciting developments are also unfolding in Indigenous communities. The T’Sou-ke First Nation on Vancouver Island is one example that built a large solar-energy system to power the community and earn significant income by selling electricity to the provincial utility.

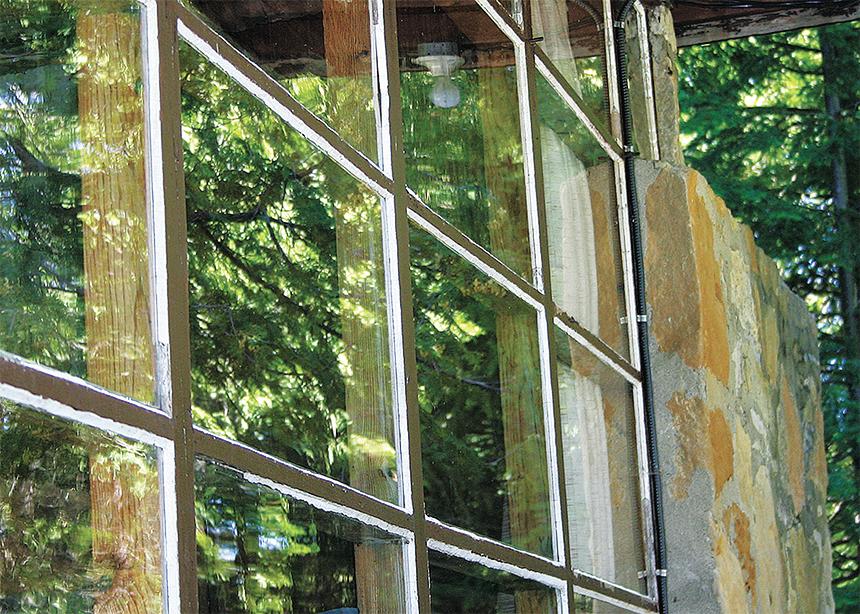

Various churches in Canada have intentionally “greened” their sacred spaces. A Presbyterian congregation in Edmonton is even initiating the country’s first multi-family, net-zero emissions housing project.

See “Going solar,” for the story of a Mennonite congregation that’s harvesting solar energy.

3. Create a plan

Each of our faith communities needs a plan. When it comes to energy production and use, we can learn from examples like the ones above. We can plan to become energy producers instead of just consumers. It’s important that these conversations engage multiple generations and people of various income levels. These plans don’t need to be complicated but they do need to show what a community values and how it intends to respond to the biblical vision of creation care.

4. Connect to local climate action plans

One of the reasons that there is such potential for Christian communities to make a difference is that our churches are part of a whole host of organizational networks. We are connected to institutions of all shapes and sizes. We need all of them to engage this challenge.

What’s more, the members of our churches can speak into organizations that have no other faith connection. We are citizens, employees, employers, non-profit volunteers, investors and consumers of both goods and services. We work and recreate in facilities with immense energy needs. Some of us attend institutions with massive endowments. All of these connections can amplify our individual convictions and facilitate transformative action.

5. Advocate for government action

Institutions are important tools for collective action and large-scale transformation. This includes the political institutions that govern our society. Why doesn’t every organization we and our churches support have a sensible energy policy? Why does our municipality, province or country not have a plan to protect the places that we love from the impacts of climate change? It’s because we haven’t told them this is important to us. Representatives of our faith communities can meet with elected leaders, tell them of our concerns and urge them to take action.

If we are communities that cultivate faith, hope and love, then we can support one another to move beyond the paralysis of inaction. (See the editorial, “Moving beyond ‘climate grief.’ ”) God’s Spirit is with us now and will be with us whatever climate change sends our way. In faith we can follow Jesus, who was and is the presence of a Creator who cares for the Earth and its creatures. And we can act, motivated by love for the places where we meet God and the places where God’s many peoples dwell.

Creation-care leaders:

• Mennonite Creation Care Network

• A Rocha Canada

• Carbon Footprint Calculator

• Greening Sacred Spaces

We invite Mennonite-related organizations and churches to post links in the comments section below to their own climate action plans, and to share what your communities of faith have already done.

![]() Scott Morton Ninomiya is a PhD candidate at the Balsillie School of International Affairs in Waterloo, Ont., a member at St. Jacobs Mennonite Church, and a Mennonite Central Committee alumnus (2000-2006).

Scott Morton Ninomiya is a PhD candidate at the Balsillie School of International Affairs in Waterloo, Ont., a member at St. Jacobs Mennonite Church, and a Mennonite Central Committee alumnus (2000-2006).

![]() Anthony G. Siegrist pastors at Ottawa Mennonite Church and is the author of the forthcoming Herald Press book Speaking of God: An Essential Guide to Christian Thought.

Anthony G. Siegrist pastors at Ottawa Mennonite Church and is the author of the forthcoming Herald Press book Speaking of God: An Essential Guide to Christian Thought.

For discussion

1. What does your family do to protect the earth, water and air in your neighbourhood? Do you consider the effects on the environment when you go about your daily chores or travel? How has our society improved our waste management in the past hundred years?

2. Anthony Siegrist and Scott Morton Ninomiya write that caring for God’s creation seems to be a divisive issue, especially when it comes to energy. Why has this become such a contentious issue? What evidence of climate change do you see? What makes us reluctant to admit the extent of the problem? What fears do you have around climate change?

3. Caring for creation can involve nurturing love for the territory of land and water around us. What are some ways we can do this? How do farmers and gardeners show friendship with the earth?

4. Has your congregation taken steps to “green” its space? Are there homes, companies or institutions in your community that have worked at this? What might be a next step for your congregation?

5. How supportive is your church of local creation-care organizations? What government action would you support in response to the climate crisis?

—By Barb Draper

Comments

I have gone to an e-bike. l also believe that we need much better bus service and connections.

Add new comment

Canadian Mennonite invites comments and encourages constructive discussion about our content. Actual full names (first and last) are required. Comments are moderated and may be edited. They will not appear online until approved and will be posted during business hours. Some comments may be reproduced in print.